- Version 1.0

- publiziert am 21. September 2022

Inhalt

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The Homeric epic

- 2.1. Research history

- 2.2. Phenomena and forms of representation

- 2.3. Perspectives for future research

- 3. Homeric heroes in the visual culture of antiquity

- 3.1. Research overview

- 3.2. Phenomena and forms of representation

- 3.3. Perspectives for future research

- 4. Einzelnachweise

- 5. Selected literature

- 6. List of images

- Citation

1. Introduction

‘Homeric heroes’ are primarily the characters of the Iliad and the Odyssey, epic poems attributed to Homer (2nd half of the 8th century BC, authorship and dating are disputed). The best-known examples are the respective protagonists Achilles (the Iliad) and Odysseus (the Odyssey). Secondarily – but not discussed in detail here – any ⟶heroes in the tradition and historical reception of the Homeric epics can be called ‘Homeric’, if, for example, Odysseus himself appears in a later work or his characteristics are given to another character. As the earliest known works of European literature and as a canonical cultural reference point in antiquity (and, with some reservations perhaps, to the present day), the Homeric epics decisively defined European notions of heroism. The Homeric heroes are not only called “heroes” (ἥρωες), but their authority as great figures of myth and prehistory, as well as their embedding in the epic genre (later called ‘heroic song’ and ‘heroic epic’), made them models of ⟶heroizations and ⟶heroisms. (Tilg)1Sections written by Stefan Tilg appear with the abbreviation (Tilg); sections written by Ralf von den Hoff appear with the abbreviation (vdH).

2. The Homeric epic

2.1. Research history

Research on Homer, which is unwieldy even for specialists, contains much disparate material on Homeric heroes. In the studies specifically devoted to the subject of heroism, however, some focal points emerge. Since Rohde in 1894, the relationship of the Homeric heroes to the Greek hero cult has been much discussed.2Rohde, Erwin: Psyche, Seelenkult und Unsterblichkeitsglaube der Griechen. 2nd ed. Freiburg 1988: Mohr. In Homer, mainly warriors, but also other persons such as the singer Demodokos (Odyssey 8,483) or the servant Moulios (Odyssey 18,423), formerly a herald, are called ἥρως. The term means something like “warrior” or “noble man”; at least on the surface level, a religious meaning or references to hero cults cannot be found. Based on this observation, Rohde and others (recently e.g. Bremmer 2006) argue that the original Greek concept of heroes was the literary one, while hero cults only developed subsequently.3Bremmer, Jan. N.: “The Rise of the Greek Hero Cult and the New Simonides”. In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 158 (2006), 15-26. Today, it is more generally accepted that the two strands coexisted from the beginning, as argued by, among others, Bravo (2009) or Jones (2011), and that they could have become intertwined soon after Homer’s death.4Bravo III J., Jorge: “Recovering the Past. The Origins of Greek Heroes and Hero Cult”. In: Albersmeier, Sabine (Ed.): Heroes. Mortals and Myths in Ancient Greece. Baltimore 2009: Yale University Press, 10-29; see also: Jones, Christopher P.: “New Heroes in Antiquity”. In: Revealing Antiquity 18 (2011). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Nagy (1999) and others argue for traces of hero cults in the Homeric heroes themselves.5Nagy, Gregory: The Best of the Achaeans. Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry. 2nd ed. Baltimore 1999: Johns Hopkins University Press.

The question of what constitutes a Homeric hero, i.e. how to characterise the Homeric ‘hero concept’, pervades all Homeric research of the 20th and 21st centuries and has recently led to Horn’s 2014 attempt at a larger systematisation.6Horn, Fabian: Held und Heldentum bei Homer. Das homerische Heldenkonzept und seine poetische Verwendung. Tübingen 2014: Narr. Following previous work, he characterises the Homeric heroes as part of an entire heroic society or heroic age whose individual members stand out in their pursuit of honour (τιμή) and (posthumous) fame/glory (κλέος). Seemingly, different heroes such as the war hero Achilles and the intellectual hero Odysseus could be derived from this common basic structure. A number of contributions see the Homeric heroes as an exaggerated reflection of the audience of the Homeric epics, aiming to construct its own identity in the epic mirror. As role models, the Homeric heroes serve here as positive or negative examples, depending on the context. Thus Effe (1988) interprets the figure of Achilles in the Iliad not primarily as a warrior hero, but as a moral figure between offended individual honour and social responsibility, a conflict from which the audience should then learn something for their own thinking and actions.7Effe, Bernd: “Der Homerische Achilleus. Zur gesellschaftlichen Funktion eines literarischen Helden”. In: Gymnasium 95 (1988), 1-16. Howie (1995) and Danek (2010) take a similar approach.8Howie, J. Gordon: “The Iliad as exemplum”. In: Andersen, Øivind / Dickie, Matthew W. (Eds.): Homer’s World. Fiction, Tradition, Reality. Athens 1995: Norwegian Institute at Athens, 141-173. The latter reads the Iliad as a “prime example of failed crisis management”, mainly because of Agamemnon’s bad decisions, which have consequences for the individual but also for the whole community.9 Danek, Georg: “Der homerische Held zwischen heroischer Monomanie und gesellschaftlicher Verantwortung”. In: Meyer, Marion / von den Hoff, Ralf (Eds.): Helden wie sie. Übermensch – Vorbild – Kultfigur. Freiburg 2010: Rombach, 67. In the original: “Paradebeispiel für missglücktes Krisenmanagement”. In a more general sense, the Homeric heroes serve as role models when their humanity and human interest are emphasised. Despite their outsized epic stature, they make basic human experiences familiar to people throughout time (Althoff 2010).10Althoff, Jochen: “Die homerischen Epen als Heldenepik”. In: Meisig, Konrad (Ed.): Ruhm und Unsterblichkeit. Heldenepik im Kulturvergleich. Wiesbaden 2010: Harrassowitz, 13-32.

Schein (1984), for example, goes so far as to interpret the war depicted in the Iliad only as a backdrop for Homer’s interpretation of existential human tragedies, limitations and hardships. The epic thus becomes a “comprehensive exploration and expression of the beauty, the rewards, and the price of human heroism”.11Schein, Seth L.: The Mortal Hero. An Introduction to Homer’s Iliad. Berkeley 1984: University of California Press, 84. Clarke (2004) extends this approach to both Homeric epics: while the Iliad problematises heroism, the Odyssey moves beyond the traditional heroic warrior ethos and shows a hero who adapts to his lowly circumstances and only through this achieves success. Thus, both epics, each in its own way, have “a deeper and more universal level, on which the miseries and exaltations of heroic experience become a device for exploring the universal realities of man’s struggle for self-validation under the immortal and carefree gods”.12Clarke, Michael: “Manhood and Heroism”. In: Fowler, Robert (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to Homer. Cambridge 2004: Cambridge University Press, 74-90, 89-90. This widespread humanist reading of the Homeric heroes is challenged by occasional post-structuralist deconstructions, such as Buchan’s 2004 scrutiny of the Odyssey. Here, the always unfulfilled desire (a category inspired by Lacan’s psychoanalysis), doubt and destruction that emanate from the Homeric heroes are emphasised.13Buchan, Mark: The Limits of Heroism. Homer and the Ethics of Reading. Ann Harbor 2004: University of Michigan Press. The phenomenon of the self-heroization of Homeric heroes in the medium of their speech has received increased interest since the 1980s. Segal (1983) and Martin (1989) have drawn attention to similarities between the Homeric heroes and their creator, the epic poet and wordsmith. Segal argues that Odysseus, through constant reference to his deeds in the past (including his long autobiographical narratives at the court of the Phaeacians in Odyssey, 9-13), creates the (posthumous) glory (κλέος) typical of the epic hero in the role of the epic bard himself.14Segal, Charles P.: “Kleos and its Ironies in the Odyssey”. In: Antiquité Classique 52 (1983), 22-47. Martin sees the Homeric heroes of the Iliad as ‘orators’ in a society in which individual excellence was also essentially defined by polished and convincing speech.15Martin, Richard P.: The Language of Heroes. Speech and Performance in the Iliad. Ithaca 1989: Cornell University Press. The Homeric heroes, and above all Achilles, thus also justify their heroism by fighting with words. (Tilg)

2.2. Phenomena and forms of representation

An essential difference between the Homeric heroes and many later heroic conceptions is that they are part of a whole society or age of heroes. The characters of the Iliad and the Odyssey are almost without exception heroes, which is reflected both in the distribution of the word ἥρως (used indiscriminately for ‘greater’ and ‘lesser’ warriors, friend and foe) and in the common code of the values of honour and glory. However, in the patriarchal world of the Homeric heroes, which is characterised by warrior nobility, it goes without saying that this refers only to noble men – women only appear in supporting roles, are not called ‘heroes’ (ἥρωες) and do not strive for fame and honour in the same way; the same applies, with few exceptions, to socially lowly figures – if, as mentioned above, the servant Moulios is nevertheless called a ‘hero’ once in the Odyssey, this is presumably due to his earlier function as a herald in war. Individual achievement is indeed evident insofar as different figures – first and foremost Achilles and Odysseus – realise the heroic concept underlying the Homeric heroes to varying degrees. However, individual heroism in the sense that a single hero faces a society of non-heroes is alien to the Homeric heroes in their world.

The situation is different when one looks at the Homeric heroes from the point of view of the narrator and his audience. The narrator of the Homeric epics repeatedly makes clear that he belongs to a later, weaker generation compared to the Homeric heroes (e.g. Iliad 12,383). He looks back to an undefined prehistory in which heroism was normal in contrast to the decadent present. From this perspective, the Homeric heroes very much stand out from an unheroic society and can accordingly be more easily understood as extraordinary figures. They are characterised by a heightening of everything humanly possible, e.g. in strength, beauty, anger, intelligence, nobility and oratory. At the same time, however, the Homeric heroes are unable to overcome the barriers that are fundamentally given to human beings. Their abilities are enhanced compared to ordinary (later) people, but they are not supernatural – in this context scholars have sometimes spoken of Homeric “realism”. Above all, however, Homeric heroes are mortal. Many have a direct or indirect divine lineage. Occasionally, the gods intervene in events for or against one of the heroes. Nevertheless, the Homeric heroes themselves do not have divine status and must deal with existential problems such as death, bitterness and the search for a home.

Honour (τιμή) and (posthumous) glory (κλέος) are the central values of the Homeric heroes, which they essentially share with their society. However, the individual realisation of these values can also bring them into conflict with society, as when Achilles, out of aggrieved honour, jeopardises the success of the entire Greek campaign against Troy. The hero of the Iliad typically realises heroic values in war. Achilles is distinguished by his “capacity for violence” (βίη). He is the strongest fighter of the Greeks, without whose participation in the war the rest of the army is helpless. Since the Iliad was created, war and ⟶violence have probably been the longest-lived and most enduring constant in the European conception of heroes; extensive descriptions of battles and duels have become part of the standard epic repertoire. Even in the 20th century, Achilles and other Homeric heroes were still perceived as war heroes, as Vandiver showed in 2010 using the example of British poetry during the First World War.16Vandiver, Elizabeth: Stand in the Trench, Achilles. Classical Receptions in British Poetry of the Great War. Oxford 2010: Oxford University Press. Nevertheless, the Odyssey demonstrates that Homeric heroes are not limited to war and violence. Odysseus is the hero who earns honour and fame through his intellect, his suffering and his adaptability. He could be called the first “new” and the first “modern” hero of European literature – it is no coincidence that the Odyssey and not the Iliad forms the subtext to James Joyce’s Ulysses. The (heroic) epic was the most important medium in which the fame of the Homeric heroes was disseminated. Without the mediating poet, the whole heroic endeavor would be in vain – an awareness of this is occasionally revealed by the Homeric heroes when they themselves speak of their posthumous fame or when the singers Phemios and Demodokos (who is himself called ἥρως) appear in the Odyssey and recount the adventures of the Homeric heroes. For the narrative construction of the Homeric heroes, the Iliad and Odyssey employ a whole arsenal of techniques that Homeric scholars have analysed, systematised and named with technical terms, e.g. “epitheta ornantia” (e.g. “the swift-footed Achilles”), “type scenes” (e.g. scenes of armour), “epic simile” and “catalogues”. They became stylistically influential for the wider epic tradition and continue to shape epic speech in the broadest sense to this day. (Tilg)

2.3. Perspectives for future research

Thanks to the considerable body of research on Homer since the 19th century, the fundamental questions regarding Homeric heroes have been clarified. Complex problems such as the relationship between literary Homeric heroes and the religious hero cult could only be solved based on new source material. An almost infinite wealth of possibilities for studying Homeric heroes, however, is offered by their history of reception. Here, one could examine the functionalisation and cycles of popularity characteristic of certain eras and contexts (such as Odysseus as a figure of the search for meaning and disorientation in the 20th century) as well as processes of transformation and hybridisation (such as Odysseus in connection with Heracles as a model for a heroization of Jesus Christ in Zilling 2011).17Zilling, Henrike M.: Jesus als Held. Odysseus und Herakles als Vorbilder christlicher Heldentypologie. Paderborn 2000: Schöningh. On a systemic level, it might be worthwhile to examine the extent to which later epics from antiquity to modern times adopt, change, counteract, etc. the ‘heroic society’ and the world of values of the Homeric heroes. Finally, although Homeric narrative techniques are already well researched, there are always new and interesting approaches from the narratological side, e.g. De Jong (1987) with the introduction of a “secondary focalization” by the characters of the Iliad, thanks to which Homeric heroes can be characterised more individually18De Jong, Irene: Narrators and Focalizers. The Presentation of the Story in the Iliad. Amsterdam 1987: Grüner.; or Grethlein (2012) with the concept of the “epic plupast”, the heroic period before the generation of Homeric heroes, which they remember, towards which they orient themselves and to which they ascribe exemplary qualities.19Grethlein, Jonas: “Homer and Heroic History”. In: Marincola, John / Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd / Maciver, Calum A. (Eds.): Greek Notions of the Past in the Archaic and Classical Eras. History without Historians. Edinburgh 2012: Edinburgh University Press, 14-36. (Tilg)

3. Homeric heroes in the visual culture of antiquity

In the visual culture of ancient Greece and Rome, Homeric heroes, i.e. the characters of the Iliad and Odyssey, were omnipresent between the 7th century BC and the 5th century AD. Their deeds appear in various visual media. They can also be found in narratives that precede or succeed the two epics in mythological chronology, such as the narratives of the so-called Epic Cycle around the ‘Trojan War’ (Cypria; Aethiopis; ‘Little Iliad’; ‘Iliou persis’ / ‘Sack of Troy’), but also as isolated, actionless-static figures. Through the lense of these representations, cycles and transformations of interest in the Homeric heroes and the heroic qualities attributed to them can be discerned. (vdH)

3.1. Research overview

The studies on ancient images of Homeric heroes are almost innumerable. The material is recorded in the lemmata of the Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae.20Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. Zürich 1981–1994: Artemis. Individual studies are available, for example, on Achilles21Kemp-Lindemann, Dagmar: Darstellungen des Achilleus in griechischer und römischer Kunst. Frankfurt a. M. 1975: Lang; Balensiefen, Lilian: “Achills verwundbare Ferse. Zum Wandel der Gestalt des Achill in nacharchaischer Zeit”. In: Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 111 (1996), 75-103; see also Latacz, Joachim: Achilleus. Wandlungen eines europäischen Heldenbildes. Stuttgart 1995: Teubner; regarding Achilles see also endnotes 49 and 50., Odysseus22Brommer, Frank: Odysseus. Die Taten und Leiden des Helden in antiker Kunst und Literatur. Darmstadt 1983: WBG; Andreae, Bernhard (Ed.): Odysseus. Mythos und Erinnerung. Mainz 1999: Philipp von Zabern; see also von den Hoff, Ralf: “Odysseus in der antiken Bildkunst”. In: Gehrke, Hans-Joachim / Kirschkowski, Mirko (Eds.): Odysseus. Irrfahrten durch die Jahrhunderte. Freiburg i. Br. 2009: Rombach, 39-64., Aias23Laimou, Anna A.: “Aίας o Tελαμώνιoς στην αρχαία ελληνική και πρώιμη ρωμαϊκή εικoνoγραφία”. In: Archaiologiki Ephemeris 138 (1999), 15-40. and Aineias24Dardenay, Alexandra: Les mythes fondateurs de Rome. Images et politique dans l’Occident romain. Paris 2010: Picard; Dardenay, Alexandra: Images des fondateurs. D’Énée à Romulus. Pessac 2012: Ausonius., but also on images related to the Odyssey, the Iliad and other Trojan epics25Ilias: Friis Johansen, Knud: The Iliad in Early Greek Art. Kopenhagen 1967: Munksgaard. – Odyssee: Touchefeu-Meynier, Odette: Thèmes odysséens dans l’art antique. Paris 1968: Boccard; Buitron-Oliver, Diana: The Odyssey and Ancient Art. An Epic in Word and Image. Annandale-on-Hudson 1992: E. C. Blum Art Institute. – redarding further Troy myths: Papadakis, Manuela: Ilias- und Iliupersisdarstellungen auf frühen rotfigurigen Vasen. Frankfurt a. M. 1994: Lang; Anderson, Michael J.: The Fall of Troy in Early Greek Poetry and Art. Oxford 1997: Clarendon; Lowenstam, Steven: As Witnessed by Images. The Trojan War Tradition in Greek and Etruscan Art. Baltimore 2008: Johns Hopkins University Press; Carpenter, Thomas H.: “The Trojan War in Early Greek Art”. In: Fantuzzi, Marco / Tsingalis, Christos (Eds.): The Greek Epic Cycle and its Ancient Reception. A Companion. Cambridge 2015: Cambridge University Press, 178-195.. Only a few surveys deal with the history of reception of Homeric heroes in ancient visual depictions comprehensively.26Latacz, Joachim: Homer. Der Mythos von Troia in Dichtung und Kunst. München 2008: Hirmer; Kunze, Christian: “Homeric Themes in Greek and Roman Sculpture”. In: Walter Karydi, Elena (Ed.): Mυθoι, κειμενα, εικoνες. Oμηρικα επη και αρχαια ελληνικη τεχην / Myths, Texts, Images. Homeric Epics and Ancient Greek Art. Ithaka 2010: Kentro Odyssiakon Spidon, 279-303; Junker, Klaus: “Ilias, Odyssee und die Bildenden Künste”. In: Rengakos, Antonios / Zimmermann, Bernhard (Eds.): Homer-Handbuch. Leben – Werk – Wirkung. Stuttgart 2011: Metzler, 395-410; see also Behr, Hans-Joachim (Ed.): Troia – Traum und Wirklichkeit. Ein Mythos in Geschichte und Rezeption. Braunschweig 2003: Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum. It is the relationship between text and image that is most extensively discussed in research.27See, for example Shapiro, Harvey A.: Myth into Art. Poet and Painter in Classical Greece. London 1994: Routledge; Giuliani, Luca: Bild und Mythos. Geschichte der Bilderzählung in der griechischen Kunst. München 2003: Beck. Debates focus on when representations of Homeric heroes first appear in the early Greek art of the 8th and 7th centuries BC and on how the first mythological images relate to the Homeric epics.28In summary: Junker, Klaus: “Zur Bedeutung der frühesten Mythenbilder”. In: Schmidt, Stefan / Oakley, John H. (Eds.): Hermeneutik der Bilder. Beiträge zur Ikonographie und Interpretation griechischer Vasenmalerei. München 2009: Beck, 65-76. According to Bernhard Schweitzer and Roland Hampe29Schweitzer, Bernhard: Herakles. Aufsätze zur griechischen Religions- und Sagengeschichte. Tübingen 1922: Mohr; Hampe, Roland: Frühe griechische Sagenbilder in Böotien. Athen 1936: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut., Homeric heroes were depicted in rare vase-paintings of the late Geometric period (750-700 BC), for example Odysseus’ shipwreck on the neck of an Attic clay jug in Munich (Staatliche Antikensammlungen Inv. 8696, see fig. 1). The interpretation of individual depictions of ‘twin beings’ played a role here, in which some wanted to recognise the sons of Actor appearing in Homer (Iliad 11, 750-52; 23, 638-42). However, this may also be a visual convention that is to be understood in a different way30Most recently Sforza, Ilaria: “Gli Attorioni Molioni e la categoria del ‘doppio naturale’: Omero, il mito e le immagini”. In: Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia 7 (2002), 297-320; Dahm, Murray K.: “Not Twins at All. The Agora Oinochoe Reinterpreted”. In: Hesperia 76 (2007), 717-730., for the contemporaneous imagery as a whole was rather dominated by generic depictions of land and ship battles, funerary ceremonies, etc., especially on large funerary vessels.31Ahlberg, Gudrun: Fighting on Land and Sea in Greek Geometric Art. Stockholm 1971: Svenska Insitutet i Athen; Ahlberg, Gudrun: Prothesis and Ekphora in Greek Geometric Art. Göteborg 1971: Åström. However, the overall less distinctive character of the geometric figures and scenes also led to the conclusion that mythical images could be recognised in all the action images of the 8th century32Webster, Thomas B. L.: “Homer and Attic Geometric Vases”. In: Annual of the British School at Athens 50 (1955), 38-50.; this is indicated by omnipresent ‘heroic’ attributes, whose extraordinary-Homeric semantics, however, remain questionable (‘Dipylon shield’).33See however: Hurwirt, Jeffrey M.: “The Dipylon Shield once more”. In: Classical Antiquity 4 (1985) 121-126; Giuliani, Luca: “Myth as past? On the Temporal Aspect of Greek Depictions of Legend”. In: Foxhall, Lin et al. (Eds.): Intentional History. Spinning Time in Ancient Greece. Stuttgart 2010: Steiner, 35-56. Finally, all figurative images of the geometric period were considered generic scenes because they consistently contradicted the Homeric epic text – as is the case on the jug in Munich; Odysseus’ shipwreck is portrayed differently in Homer.34Friis Johansen, Karsten: Ajas und Hektor. Ein vorhomerisches Heldenlied? Kopenhagen 1961: Munksgaard; Friis Johansen: “Iliad”, 1967; Coldstream, John N.: Geometric Greece. London 1977: Methuen, 352-356; concerning the jug in Munich see already: Kirk, Geoffrey: “Ships on Geometric Vases”. In: Annual of the British School in Athens 44 (1949), 93-153; Brunnsåker, Sture: “The Pithecusean Shipwreck. A Study of a Late Geometric Picture and Some Basic Aesthetic Concepts of the Geometric Figure-style”. In: Opuscula Romana 4 (1962), 165-242; most recently Giuliani: “Bild und Mythos”, 2003, 73-75; Hurwit, Jeffrey M.: “The Shipwreck of Odysseus. Strong and Weak Imagery in Late Geometric Art”. In: American Journal of Archaeology 115 (2011), 1-18. According to this opinion, the first mythological images did not appear until the first half of the 7th century BC. Carter’s and Fittschen’s studies took a mediating position in this debate.35Fittschen, Klaus: Untersuchungen zum Beginn der Sagendarstellungen bei den Griechen. Berlin 1969: Hessling; Carter, John: “The Beginnings of Narrative Art in the Geometric Period”. In: Annual of the British School in Athens 67 (1972), 25-58; see also Ahlberg-Cornell, Gudrun: Myth and Epos in Early Greek Art. Jonserd 1992: Åström. The formal influence of oriental artefacts on the visual representation was also considered. Lastly, Snodgrass showed that images in the sense of illustrations of specific Homeric narratives cannot be identified before the 7th century BC.36Snodgrass, Anthony: Homer and the Artists. Text and Picture in Early Greek Art. Cambridge 1998: Cambridge University Press, with a review by Luca Giuliani in: Gnomon 73 (2001) 428-433; regarding the early reception of Homer in images cf. already: Kannicht, Richard: “Dichtung und Bildkunst. Die Rezeption der Troja-Epik in den frühgriechischen Sagenbildern”. In: Brunner, Helmut (Ed.): Wort und Bild. München 1979: Fink, 279-296; Kannicht, Richard: “Poetry and Art. Homer and the Monuments Afresh”. In: Classical Antiquity 1 (1982), 70-86; Cook, Robert M.: “Art and Epic in Archaic Greece”. In: Bulletin antieke beschaving 58 (1983), 1-6.

More recently, other research perspectives have emerged. Giuliani adopted a narratological perspective37Giuliani: “Bild und Mythos”, 2003.: He described the scenic images of the 8th century BC as ‘descriptive’ in that they showed – similar to the description of the shield of Achilles in the Iliad (18, 477-608) – the state and condition of the world. Only through the depiction of extraordinary objects (Trojan horse on wheels) or deeds (blinding a drunken giant), which do not occur ‘in the world’, did this change – probably under the influence of Homer – in the earlier 7th century BC to a ‘narrative’ style of representation, which required the naming of the actors (heroes) and unambiguous stories. Langdon, on the other hand, interpreted the geometric images (“released from the shadow of Homer”38Langdon, Susan: Art and Identity in Dark Age Greece, 1100–700 B.C.E. Cambridge 2008: Cambridge University Press (quote p. 4).) in a structuralist perspective as negotiations of social identities and ‘rites de passages’.

The following images of Homeric heroes, often named in inscriptions from the 7th century until the 4th century BC, have almost always been studied in the context of the pictorial corpus of all Greek myths about gods and heroes39A comprehensive overview is also provided by: Schefold, Karl: Frühgriechische Sagenbilder. München 1964: Hirmer; Schefold, Karl: Götter- und Heldensagen der Griechen in der spätarchaischen Kunst. München 1978: Hirmer; Schefold, Karl / Jung, Franz: Die Sagen von den Argonauten, von Theben und Troia in der klassischen und hellenistischen Kunst. München 1989: Hirmer; Schefold 1993; Schefold, Karl: Götter- und Heldensagen der Griechen in der früh- und hocharchaischen Kunst. München 1993: Hirmer., and more recently also in the context of generic representations (‘life images’) that were contemporaneous and often closely related to them typologically. In the process, they have been explained – like myths per se in the early Greek period – as visual debates about problematic situations, norms, relevant social practices, role models and practices of the living world.40Cf. the works of Tonio Hölscher, e.g. Hölscher, Tonio: Aus der Frühzeit der Griechen. Räume – Körper – Mythen. Stuttgart 1998: Teubner; Hölscher, Tonio: “Myths, Images, and the Typology of Identities in Early Greek Art”. In: Gruen, Erich S. (Ed.): Cultural Identity in the Ancient Mediterranean. Los Angeles 2011: Getty Research Institute, 47-65; see also Giuliani, Luca: “Mythen-versus Lebensbilder? Vom begrenzten Gebrauchswert einer beliebten Opposition”. In: Dally, Ortwin et al. (Eds.): Medien der Geschichte. Antikes Griechenland und Rom. Berlin 2014: de Gruyter, 204-226. Junker concluded that many images of Homeric heroes of the 6th and 5th centuries BC represent “pseudo-Homerica”, i.e. they took up Homeric names and themes, but mainly attracted attention by building on and further developing their ‘Homeric’ content.41Junker, Klaus: Pseudo-Homerica. Kunst und Epos im spätarchaischen Athen. Berlin 2003: de Gruyter.

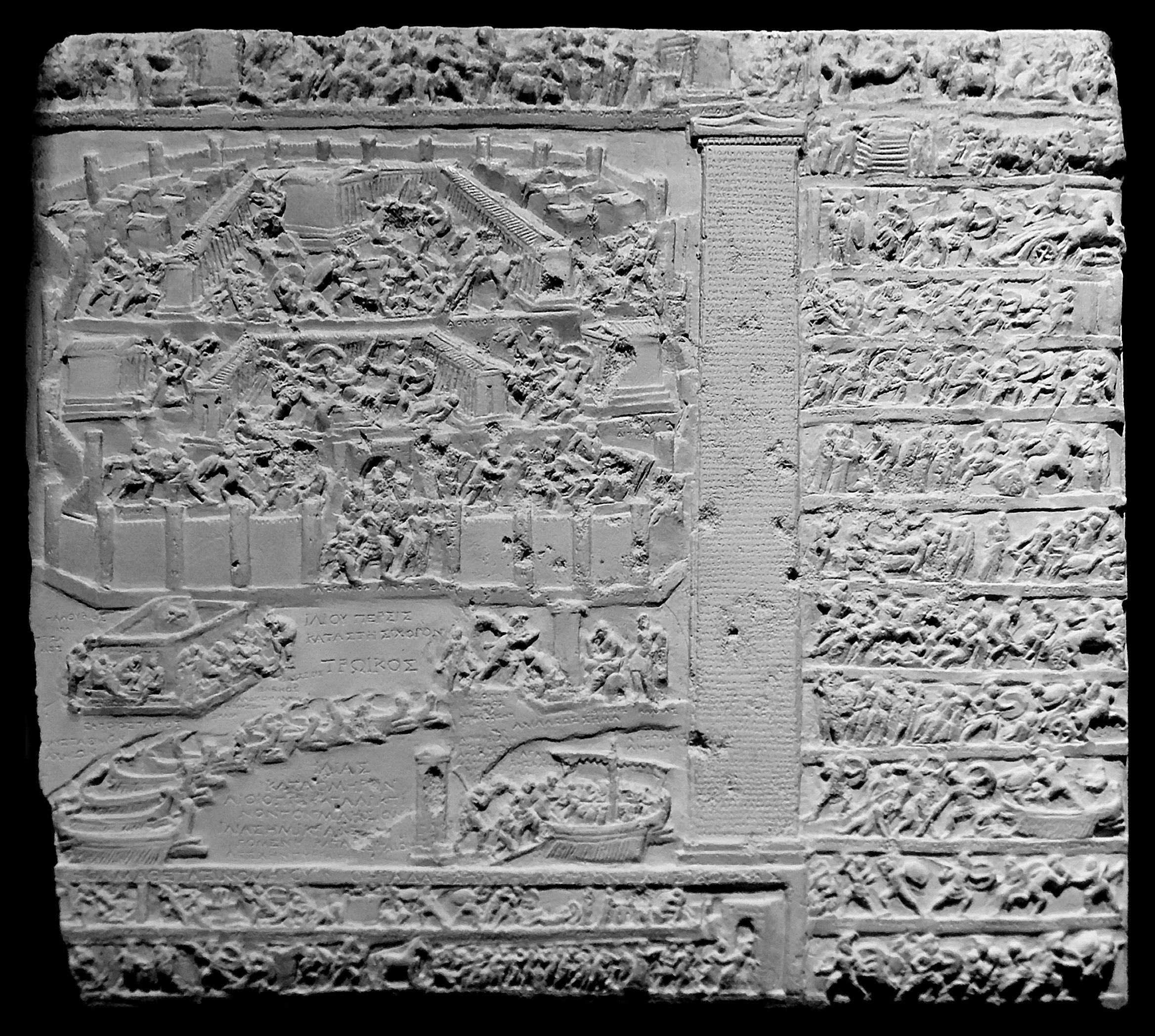

Images of Homeric heroes from more recent periods have found little specific research interest, such as in Hellenistic pottery (‘Homeric cups’)42Sinn, Ulrich: Die homerischen Becher. Hellenistische Reliefkeramik aus Makedonien. Berlin 1979: Mann; Giuliani: “Bild und Mythos”, 2003, 263-280., as decoration of Roman villas in reliefs (‘Tabulae Iliacae’)43Valenzuela Montenegro, Nina: Die Tabulae Iliacae. Mythos und Geschichte im Spiegel einer Gruppe frühkaiserzeitlicher Miniaturreliefs. Berlin 2002: dissertation.de; Squire, Michael: The Iliad in a Nutshell. Visualizing Epic on the Tabulae Iliacae. Oxford 2011: Oxford University Press., sculptures (Villa of Sperlonga)44Andreae, Bernhard: Odysseus. Archäologie des europäischen Menschenbildes. Frankfurt a. M. 1982: Societaets-Verlag; Andreae, Bernhard: Praetorium speluncae. Tiberius und Ovid in Sperlonga. Stuttgart 1994: Steiner; Himmelmann, Nikolaus: Sperlonga. Die homerischen Gruppen und ihre Bildquellen. Opladen 1995: Westdeutscher Verlag; de Grummond, Nancy / Ridgeway, Brunilde S.: From Pergamon to Sperlonga. Sculpture and Context. Berkeley 2000: University of California Press; vgl. zudem Kunze, Christian: “Zur Datierung des Laokoon und der Skyllagruppe aus Sperlonga”. In: Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 111 (1996), 139-223. and wall paintings.45Biering, Ralf: Die Odysseefresken vom Esquilin. München 1994: Biering & Brinkmann. Late antique and early medieval representations of Odysseus have also been re-examined.46Moraw, Susanne: “Odysseus”. In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum, vol. 26. Stuttgart 2015: Hiersemann, 76-92; Moraw, Susanne: “Vom männlichen Bestehen einer Gefahr zur Ideologie der totalen Vernichtung. Scylla and the Sirens from Homer to Herrad von Hohenburg”. In: Visual Past 2.1 (2015), 89-135. (vdH)

3.2. Phenomena and forms of representation

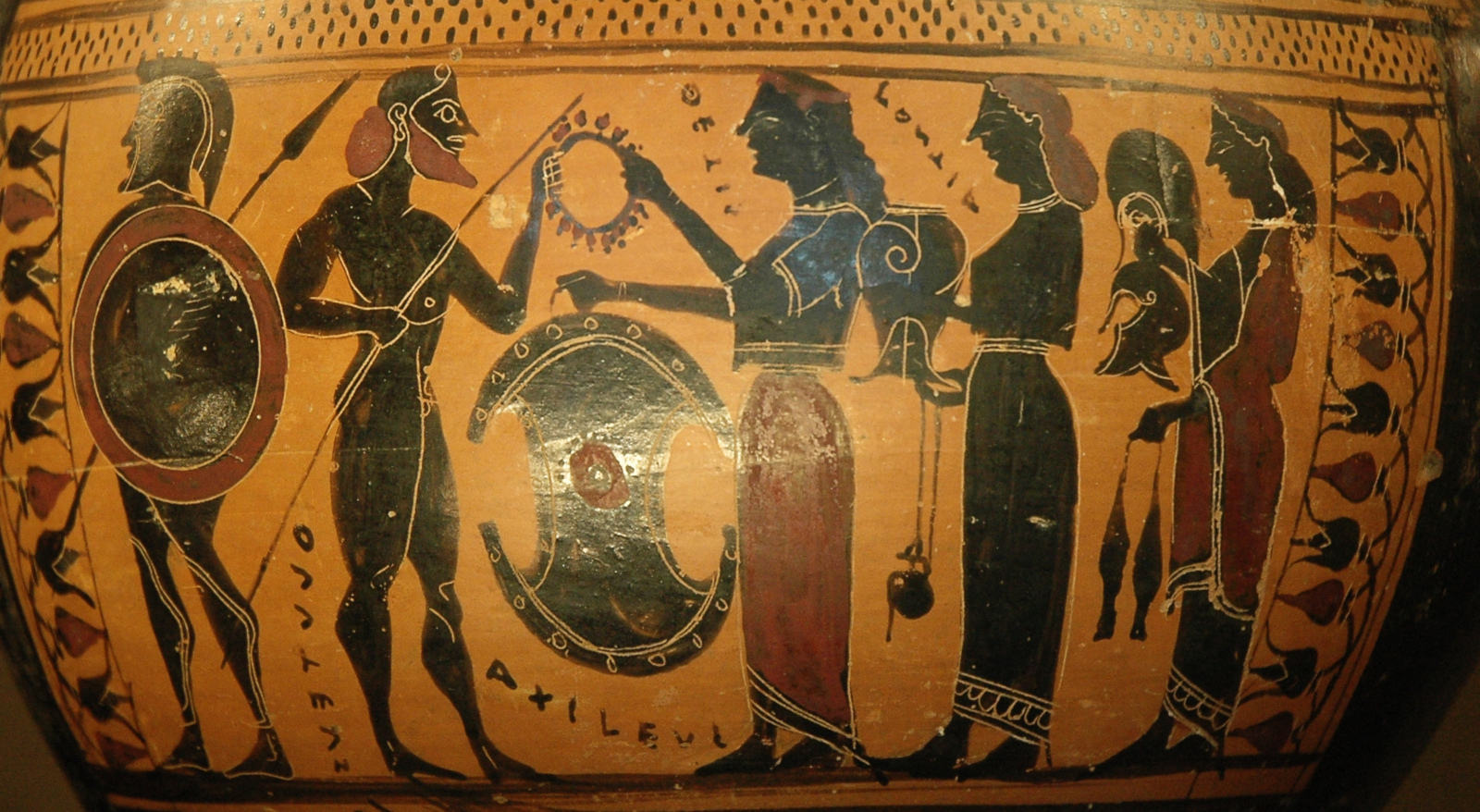

The emergence of the written Homeric epics from the oral tradition and the appearance of visual representations of their protagonists, whom Homer consistently refers to as heroes, seem to have proceeded simultaneously, even if they cannot be dated exactly, during the emergence of mythological imagery in Greece during the period around and after 700 BC. Direct dependencies or primary inspiration by Homer can hardly be proven. In quantitative terms, Odysseus stood out from circa 670 BC as the first Homeric hero to be figuratively portrayed, with his ⟶collective achievements (Odyssey 9, 166-566: blinding of Polyphemus, see fig. 2; escape from his cave) being of particular interest.47Cf. von den Hoff, Ralf: “Odysseus. An Epic Hero with a Human Face”. In: Albersmeier, Susanne (Ed.): Heroes. Mortals and Myths in Ancient Greece. Baltimore 2009: Walters Art Museum, 57-65. This was followed in the later part of the 7th century BC by Patroclus, Menelaus and Achilles, for example, and from the 6th century BC on by a large number of other Homeric figures such as Aias, Paris, Hector, Agamemnon, Sarpedon, etc. In terms of content, the focus increases on depictions of warriors at their departure (fig. 4), in battle (fig. 3) and as fallen. There are close connections to non-Homeric scenes until the 5th century BC.48Spieß, Angela B.: Der Kriegerabschied auf attischen Vasen der archaischen Zeit. Frankfurt a. M. 1992: Lang; Ellinghaus, Christian: Aristokratische Leitbilder – demokratische Leitbilder. Kampfdarstellungen auf athenischen Vasen in archaischer und frühklassischer Zeit. Münster 1997: Scriptorium; Recke, Matthias: Gewalt und Leid. Das Bild des Krieges bei den Athenern im 6. und 5. Jh. v. Chr. Istanbul 2002: Ege Yayınları. Homeric heroes also appear in many other situations: Achilles’ revengeful desecration of Hector’s corpse (Iliad 22, 395-404) was especially popular in the 6th and early 5th centuries BC49von den Hoff, Ralf: “‘Achill, das Vieh’? Zur Problematisierung transgressiver Gewalt in klassischen Vasenbildern”. In: Fischer, Günter / Moraw, Susanne (Eds.): Die andere Seite der Klassik. Gewalt im 5. und 4. Jahrhundert v. Chr. Stuttgart 2005: Steiner, 225-246; e.g. on an Attic hydria, c. 520/10 BC, in Boston, Museum of Fine Arts Inv. 63.473. Online at: https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153447/ (accessed on 22.04.2022); concerning images of violence cf. Blome, Peter: “Das Schreckliche im Bild”. In: Graf, Fritz (Ed.): Ansichten griechischer Rituale. Geburtstags-Symposium für Walter Burkert. Stuttgart 1998: Steiner, 72-95; Muth, Susanne: Gewalt im Bild. das Phänomen der medialen Gewalt im Athen des 6. und 5. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. Berlin 2008: de Gruyter, 93-133; Giuliani, Luca: “Helden-Hybris”. In: von den Hoff, Ralf / Meyer, Marion (Eds.): Helden wie sie. Übermensch – Vorbild – Kultfigur in der griechischen Antike. Freiburg i. Br. 2009: Rombach: 193-214.; until the 5th century BC, the ransoming of Hector’s body (Iliad 24) is shown as a scene of Achilles’ ‘hubris’ at a meal.50Giuliani, Luca: “Kriegers Tischsitten, oder die Grenzen der Menschlichkeit. Achill als Problemfigur”. In: Hölkeskamp, Karl Joachim et al. (Eds.): Sinn (in) der Antike. Orientierungssysteme, Leitbilder und Wertkonzepte im Altertum. Mainz 2003: Philipp von Zabern, 135-161; cf. the depiction on the skyphos of the ‘Brygos Painter’, c. 490 BC, in Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum Inv. IV 3710. Online at https://www.khm.at/objektdb/detail/56696/ (accessed on 01.09.2018). Conversely, there are also genre-like scenes51Himmelmann, Nikolaus: Der ausruhende Herakles. Paderborn 2009: Schöningh, 88-121.: Achilles is depicted tending to the wounded Patroclus (fig. 5).52Junker: “Pseudo-Homerica”, 2003, 2-8; on this drinking bowl see Dorka Moreno, Martin: “Achilles, Patroklos and Herakles. Conceptions of kλέος on the So-Called Sosias Cup”. In: Helden. Heroes. Héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen, Special Issue 2 (2016), 17-25. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2016/QMR/04. A board game between Aias and Achilles is the most popular Achilles theme from about 530 to the early 5th century BC (fig. 6), although we know of no textual reference.53Mommsen, Heide: “Achill und Aias pflichtvergessen?” In: Cahn, Herbert Adolph et al. (Eds.): Tainia. Roland Hampe zum 70. Geburtstag. Mainz 1980: Philipp von Zabern, 139-152; Woodford, Susan: “Ajax and Achilles Playing a Game on an Olpe in Oxford”. In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies 102 (1982), 173-185; Junker: “Pseudo-Homeric”, 2003, 8-16. Homeric heroes are thus shown, without being given a special status compared to other mythological figures, as representatives of aristocratic ideals and ways of life (war; agon; revelry), later also of democratic values (dispute over Achilles’ weapons at a voting scene54Kunze, Christian: “Dialog statt Gewalt. Neue Erzählperspektiven in der frühklassischen Vasenmalerei”. In: Fischer, Günther / Moraw, Susanne (Eds.): Die andere Seite der Klassik. Gewalt im 5. und 4. Jahrhundert v. Chr. Stuttgart 2005: Steiner, 45-71.) or paradigmatic, but not least also problematic, transgressive situations (revenge; suicide; violence). The fact that basic questions of dealing with fame (kleos) were also visually thematised has recently been established.55Dorka Moreno: “Achilles, Patroklos and Herakles”, 2016.

All in all, scenes with Homeric heroes never make up more than 30% of the Greek mythological imagery from the 7th to the 5th centuries BC.56Snodgrass: “Homer and the Artists”, 1998, 141. Heracles was far more popular than Achilles – especially in Athens –, so Homer’s figures shaped visual culture far less, and far less frequently in terms of their successes in martial combat, than Homer’s esteemed reputation might lead one to expect.

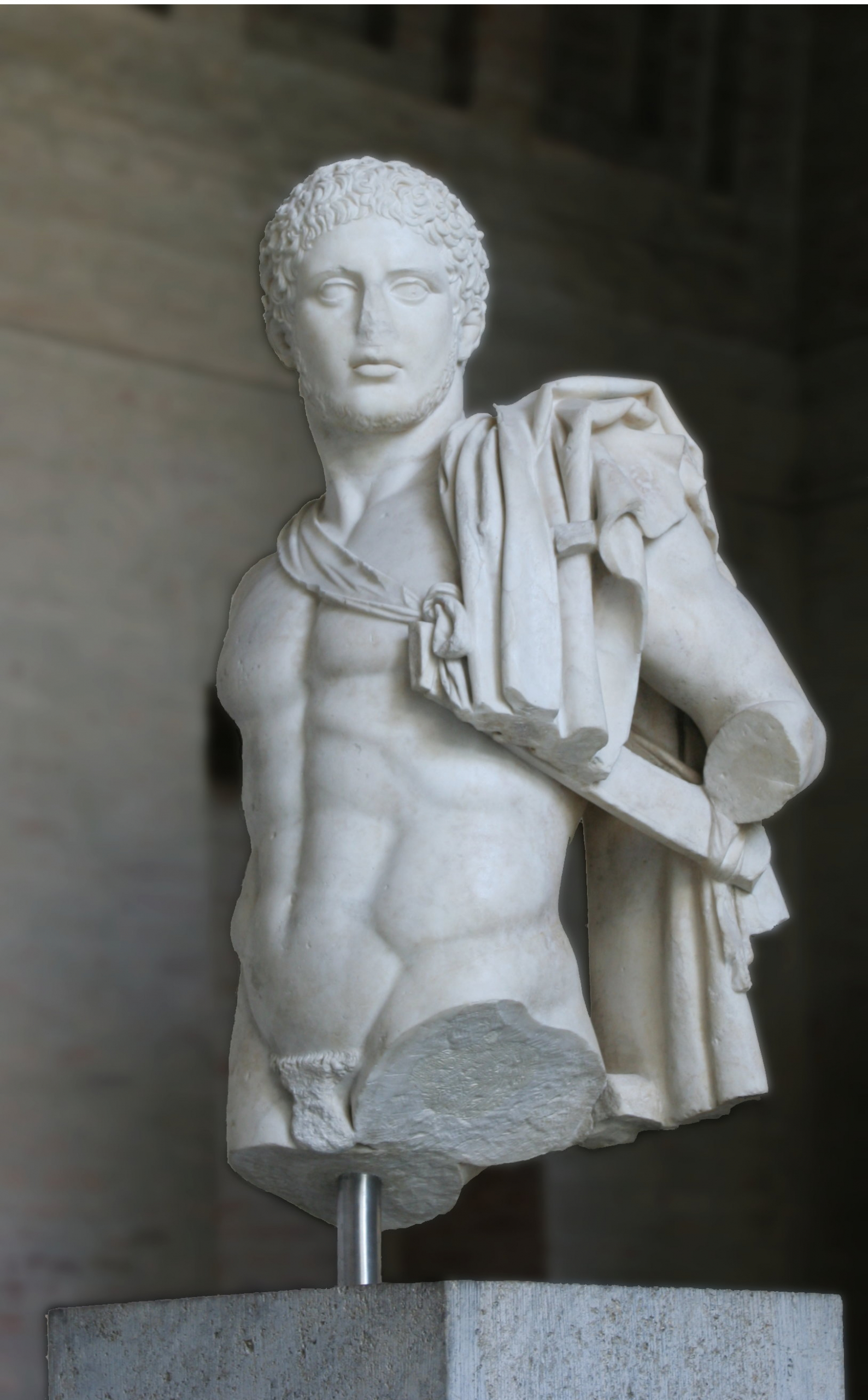

Until the end of the 5th century BC, images of Homeric heroes, like those of all myths, dominated paintings on luxury ceramics, ornaments on utensils and weapons, and from the 6th century BC on, elaborate architecture such as temples. Statuary representations of Homeric heroes are rare. For example, a statue of Penelope from the early 5th century BC and a statue of Diomedes from the later 5th century BC have survived in Roman copies, showing him with the Palladion stolen from Troy, an episode of the so-called ‘Little Iliad’ (fig. 7).57Penelope: Hölscher, Tonio: “Penelope für Persepolis, oder: Wie man einen Krieg gegen den Erzfeind beendet”. In: Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 126 (2011), 33-76; see also “396 Penelope”. In: iDAIObjects/Arachne. Online at: http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/typus/396 (accessed on 01.09.2018) – Diomedes: Landwehr, Christa: “Juba II. als Diomedes?” In: Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 107 (1992), 103-124; see also “170 Diomedes Cuma – München”. In: iDAIObjects/Arachne. Online at: http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/typus/170 (accessed on 09.01.2018), and Hildebrandt, Frank: “Diomedes, tauglich für die römische Herrschaftsikonogaphie?” In: Ganschow, Thomas (Ed.): Otium. Festschrift für Volker Michael Strocka. Remshalden 2005: Greiner, 149-153. The well-known ‘Doryphoros’, a work of Polykleitos from the mid-5th century BC, is sometimes identified as Achilles, but this is not confirmed.58Most recently with older literature: Vollmer, Cornelius: “Eine Allegorie der Demokratie? Zur Benennung des polykletischen Doryphoros”. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. Athenische Abteilung 129–130 (2014–15), 125-146; besides Achilles, Orestes or Polydeukes are sometimes recognised in the ‘Doryphoros’; see also „191 Doryphoros“. In: iDAIObjects/Arachne. Online at: http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/typus/191 (accessed on 01.09.2018). – A bronze replica of the Doryphoros served as a memorial to the fallen of the First World War at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich from 1920/21: Schneider, Rolf M.: “Polyklet: Forschungsbericht und Antikenrezeption”. In: Beck, Hans et al. (Eds.): Polyklet. Der Bildhauer der griechischen Klassik. Mainz 1990: Philipp von Zabern, 485-494. Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) referred to Achilles as a model, but there is no evidence of any pictorial work that explicitly demonstrates this.59Stewart, Andrew: Faces of Power. Alexander’s Image and Hellenistic Politics. Berkeley 1993: University of California Press, esp. 78-86; critical of the connections between Alexander and Achilles: Heckel, Waldemar: “Alexander, Achilles and Heracles. Between Myth and History”. In: Wheatley, Pat / Baynham, Elisabeth (Eds.): East and West in the World Empire of Alexander. Essays in Honor of Brian Bosworth. Oxford 2015: Oxford University Press, 21-34. Pliny the Elder reports in the 1st century AD (naturalis historia 34, 18) that statues of naked men with lances were called effigies Achilleae, i.e. Achilles was regarded as a model for the athletically trained warrior and athlete. However, ⟶prefigurative images relating to Homeric heroes played a subordinate role in Roman portraiture.60Wrede, Henning: Consecratio in formam deorum. Vergöttlichte Privatpersonen in der römischen Kaiserzeit. Mainz 1981: Philipp von Zabern; Maderna, Caterina: Iuppiter, Diomedes und Merkur als Vorbilder für römische Bildnisstatuen. Heidelberg 1988: Verlag Archäologie und Geschichte; see also Hildebrandt: “Diomedes”, 2005.

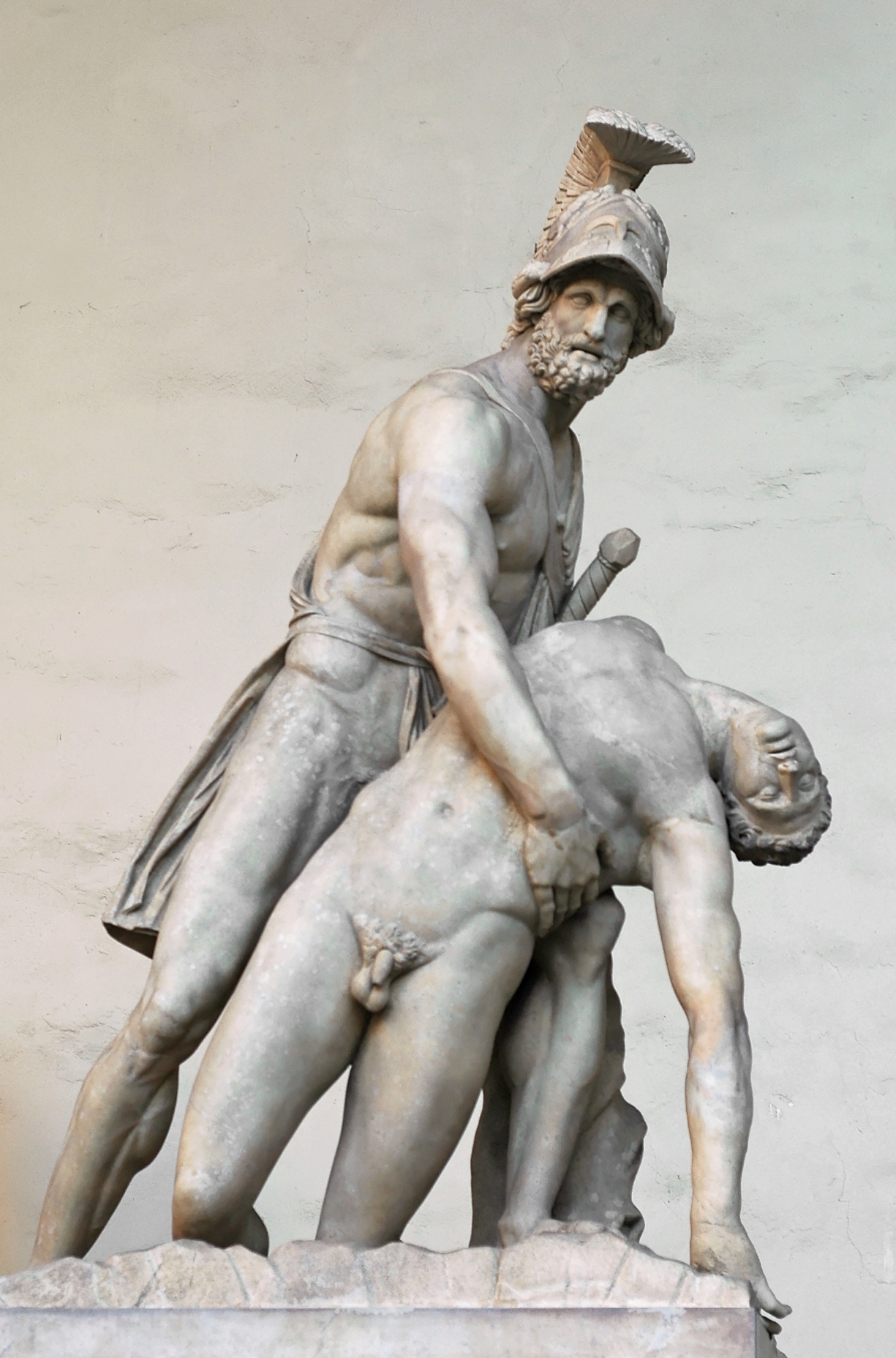

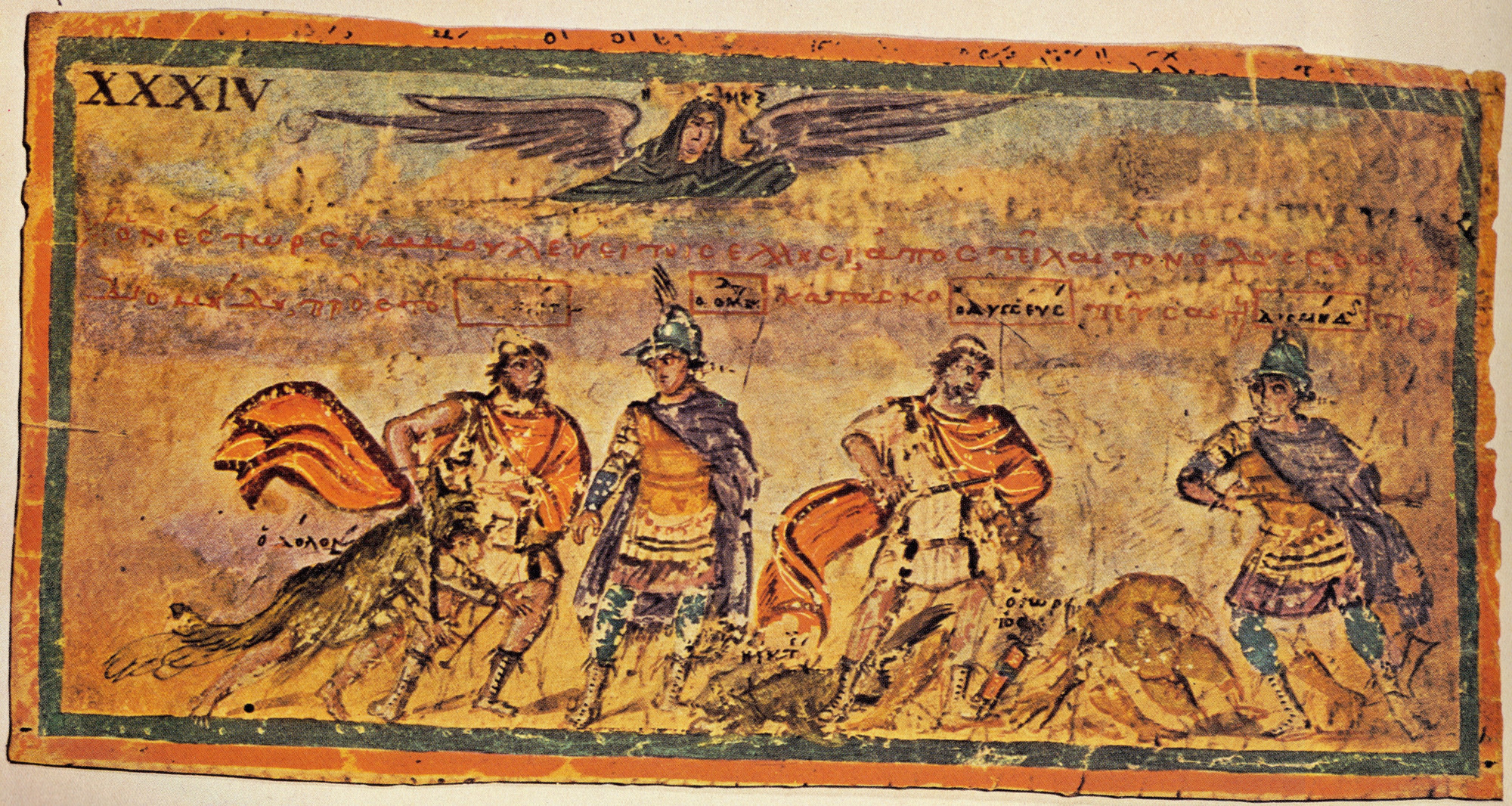

A different kind of interest, more focused on illustration, is visible from the 3rd/2nd century BC onwards in narratively broader, cyclical depictions from the epics, as on the ‘Homeric cups’ or on the 1st century BC ‘Tabulae Iliacae’ (fig. 8), then also in Roman wall painting (Odyssey frescoes from the Esquiline in Rome, c. 40 BC).61See endnote 43. In the Hellenistic period, sculptures were created that presented Homer’s heroes scenically, freely and on a large scale, such as the ‘Pasquino Group’, which depicts Aias with the body of Achilles or Menelaus with that of Patroclus (fig. 9)62Pasquino: Wünsche, Raimund: “Pasquino”. In: Münchner Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst 42 (1991), 7-38; with another designation: Weis, Anne: “The Pasquino Group and Sperlonga. Menelaos and Patroklos or Aeneas and Lausus (Aen. 10, 791-832)?” In: Στεφανoς. Studies in Honor of Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway. Philadelphia 1998: University Museum Publications, 255-286; see also “395 Pasquino-Gruppe”. In: iDAIObjects/Arachne. Online at: http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/typus/395 (accessed on 01.09.2018)., and Achilles holding the dying Amazon Penthesilea.63Grassinger, Dagmar: “Die Achill-Penthesilea-Gruppe sowie die Pasquino-Gruppe und ihre Rezeption in der Kaiserzeit”. In: Hellenistische Gruppen. Gedenkschrift für Andreas Linfert. Mainz 1999: Philipp von Zabern, 323-330; see also iDAIObjects/Arachne. Online at: http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/typus/753; http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/typus/754 (accessed on 01.09.2018). Reinforced by the emergence of large villas with rich pictorial decoration, especially in Italy, copies of these sculptures and newly designed larger figure ensembles were created, such as the sculptures in the grotto of the villa near Sperlonga around 30 BC, which staged an ‘Odyssey in marble’ (figs. 10-11).64See endnote 44. Since the 1st century BC, Aineias (Latin Aeneas) has been depicted more frequently in Rome as the founding hero of that city and the ancestor of the Iulian family from which Caesar and Augustus were descended, and has subsequently become an exemplar of Roman virtue (virtus) and Romanitas65Dardenay: “Les mythes fondateurs de Rome”, 2010; Dardenay: “Images des fondateurs”, 2012., for example on funerary monuments in the provinces. On coinage Italic families referred genealogically to other Homeric heroes as did cities in Asia Minor to Homeric traditions.66Münzen: Pause-Dreyer, Ursula: Die Heroen des Trojanischen Krieges auf griechischen Münzen. München 1975: Universität München; Lindner, Ruth: Mythos und Identität. Studien zur Selbstdarstellung kleinasiatischer Städte in der römischen Kaiserzeit. Stuttgart 1994: Steiner; Krumme, Michael: Römische Sagen in der antiken Münzprägung. Marburg 1995: Hitzeroth; Böhm, Stephanie: Die Münzen der Römischen Republik und ihre Bildquellen. Mainz 1997: Philipp von Zabern. – Funerary buildings: Lorenz, Susanne M.: Untersuchungen zum römischen Gründungsmythos in der Sepulkralkunst. Dissertation Heidelberg 2001: Universität Heidelberg. Online at: https://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/volltextserver/20642/1/Diss_Lorenz_PDFA.pdf (accessed on 01.09.2018). When relief sarcophagi with mythological scenes appeared as burial sites in the Roman Empire from around 120 AD onwards, Homeric heroes became a popular theme, especially in Greece, to illustrate the qualities of the deceased in relation to their heroic past.67Koortbojian, Michael: Myth, Meaning, and Memory on Roman Sarcophagi. Berkeley 1995: University of California Press; Rogge, Sabine: Die attischen Sarkophage 1. Achill und Hippolytos. Berlin 1995: Mann; Zanker, Paul / Ewald, Björn (Eds.): Mit Mythen leben. Die Bilderwelt der römischen Sarkophage. München 2004: Hirmer; see also: Moraw, Susanne: “Odysseus in der Sepulkralkunst der Stadt Rom. Eine Allegorie für die menschliche Seele?” In: Eich, Armin et al. (Eds.): Das dritte Jahrhundert. Kontinuitäten, Brüche, Übergänge. Stuttgart 2017: Steiner, 123-146, and the following note. Odysseus and the Sirens appeared on Italian sarcophagi in the 3rd century.68Ewald, Björn C.: “Das Sirenenabenteuer des Odysseus, ein Tugendsymbol? Überlegungen zur Adaptabilität eines Mythos”. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. Römische Abteilung 105 (1998), 227-258; Moraw: “Vom männlichen Bestehen einer Gefahr”, 2015. Scenes from the Vita of Achilles (‘Tensa Capitolina’)69Ghedini, Francesca: Il carro dei Musei Capitoloni. Epos e mito nella società tardo antica. Rom 2009: Quasar. were depicted on bronze fittings of a magnificent chariot in Rome at that time; metal tableware was showing the Achilles Vita until the 6th century (fig. 12).70Kaufmann-Heinimann, Annemarie / Furger, Alex R.: Der Silberschatz von Kaiseraugst. Augst 1984: Römermuseum, 225-307, catalogue no. 63 tab. 146-160; Hengel, Martin: Achilleus in Jerusalem. Eine spätantike Messingkanne mit Achilleus-Darstellungen aus Jerusalem. Heidelberg 1982: Winter. Around 500 AD, the Iliad was illustrated in a text edition in Alexandria or Constantinople (‘Ilias Ambrosiana’, fig. 13).71Bianchi-Bandinelli, Ranuccio: Hellenistic-Byzantine Miniatures of the Iliad. Ilias Ambrosiana. Olten 1955: Graf; Weitzmann, Kurt: Spätantike und frühchristliche Buchmalerei. München 1977: Prestel, 44-51. Procopius’ claim that the statue of the Eastern Roman Emperor Iustinian (527–565) at the Augusteion in Constantinople shows him in the schema Achilleion (de aedificiis 1, 2, 7-12) provides late evidence for the prefigurative character of Homeric heroes for the image of rulers. Depictions of Odysseus in the Siren Adventure represent a bridge to the Middle Ages’ pictorial tradition.72Moraw: “Vom männlichen Bestehen einer Gefahr”, 2015. (vdH)

3.3. Perspectives for future research

A comprehensive study of visual representations of Homeric heroes in antiquity is lacking. Research on the creation of such images in Homer’s time and after has so far concentrated on the relationships between images and texts, rather than on examining the early pictorial concepts for the depiction of extraordinary figures.73For example Junker: “Pseudo-Homerica”, 2003; Hurwit: “Shipwreck of Odysseus”, 2011; von den Hoff, Ralf: “Vom Heros erzählen. Visuelle Strategien der Heldennarration im antiken Griechenland”. In: Heinemann, Alexander et al. (Eds.): Image – Narration – Context. Visual Narration in Culutures and Societies of the Old World. Heidelberg 2019: Propylaeum. Online at: https://books.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/propylaeum/series/info/favis (accessed on 07.09.2018). The role of visual media in the heroization of individual Homeric actors and in heroisms related to them has therefore been reflected less than the reception of Homer. On the other hand, there are no systematic studies on whether and how images of heroes made use of certain pictorial formulae to indicate extraordinariness, for example through Homerising antiquaria74Neils, Jennifer: “Hera, Paestum, and the Cleveland Painter”. In: Marconi, Clemente (Ed.): Greek Vases. Images, Contexts and Controversies. Leiden 2004, Brill, 78-81; on ‘mythicising’ antiquaria see also: Schäfer, Thomas: Andres Agathoi. Studien zum Realitätsgehalt der Bewaffnung attischer Krieger auf Denkmälern klassischer Zeit. München 1998: tuduv; Giuliani, Luca: “Myth as past? On the temporal aspect of Greek depictions of legend”. In: Foxhall, Lin et al. (Eds.): Intentional History. Spinning Time in Ancient Greece. Stuttgart 2010: Steiner, 35-56. or by integrating local heroes into scenes with Homeric heroes.75Thus the Attic heroes Demophon and Akamas often appeared in Homeric scenes in Athens in the 5th century BC (for literature on this see note 25). In the Troad, Homeric images were used as a means of establishing identity: Lindner: “Mythos und Identität”, 1994; Özgünel, Coşkun: “Das Heiligtum des Apollon Smintheus und die Ilias”. In: Studia Troica 13 (2003), 261-291. – On such phenomena see also Erskine, Andrew: Troy between Greece and Rome. Local Tradition and Imperial Power. Oxford 2001: Oxford University Press. Homeric heroes were visualised in antiquity on the one hand as models of honorable and thus glorious action. On the other hand – and this especially until the 4th century BC – they appeared as figures of a mythological discourse about norms and ideals of action, which by no means received the character of postive role models: Dangers of honor and fame or hubris were also visually negotiated, problematic heroes were just as important as exemplary ones. Other factors can be recognised in the Hellenistic and in the Roman imperial periods: Homeric heroes were now conceived as exempla, for example in forms of the imitatio heroica. Furthermore, they were depicted as actors in cyclical, narrative sequences of the epic, the representation of which was obviously linked to ideas of education and prestige in the Greek literary tradition. Links and boundaries between these phenomena could be examined more closely in order to better understand phenomena of heroization as well as those of the exemplarity of Homeric heroes. (vdH)

4. Einzelnachweise

- 1Sections written by Stefan Tilg appear with the abbreviation (Tilg); sections written by Ralf von den Hoff appear with the abbreviation (vdH).

- 2Rohde, Erwin: Psyche, Seelenkult und Unsterblichkeitsglaube der Griechen. 2nd ed. Freiburg 1988: Mohr.

- 3Bremmer, Jan. N.: “The Rise of the Greek Hero Cult and the New Simonides”. In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 158 (2006), 15-26.

- 4Bravo III J., Jorge: “Recovering the Past. The Origins of Greek Heroes and Hero Cult”. In: Albersmeier, Sabine (Ed.): Heroes. Mortals and Myths in Ancient Greece. Baltimore 2009: Yale University Press, 10-29; see also: Jones, Christopher P.: “New Heroes in Antiquity”. In: Revealing Antiquity 18 (2011). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- 5Nagy, Gregory: The Best of the Achaeans. Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry. 2nd ed. Baltimore 1999: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- 6Horn, Fabian: Held und Heldentum bei Homer. Das homerische Heldenkonzept und seine poetische Verwendung. Tübingen 2014: Narr.

- 7Effe, Bernd: “Der Homerische Achilleus. Zur gesellschaftlichen Funktion eines literarischen Helden”. In: Gymnasium 95 (1988), 1-16.

- 8Howie, J. Gordon: “The Iliad as exemplum”. In: Andersen, Øivind / Dickie, Matthew W. (Eds.): Homer’s World. Fiction, Tradition, Reality. Athens 1995: Norwegian Institute at Athens, 141-173.

- 9Danek, Georg: “Der homerische Held zwischen heroischer Monomanie und gesellschaftlicher Verantwortung”. In: Meyer, Marion / von den Hoff, Ralf (Eds.): Helden wie sie. Übermensch – Vorbild – Kultfigur. Freiburg 2010: Rombach, 67. In the original: “Paradebeispiel für missglücktes Krisenmanagement”.

- 10Althoff, Jochen: “Die homerischen Epen als Heldenepik”. In: Meisig, Konrad (Ed.): Ruhm und Unsterblichkeit. Heldenepik im Kulturvergleich. Wiesbaden 2010: Harrassowitz, 13-32.

- 11Schein, Seth L.: The Mortal Hero. An Introduction to Homer’s Iliad. Berkeley 1984: University of California Press, 84.

- 12Clarke, Michael: “Manhood and Heroism”. In: Fowler, Robert (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to Homer. Cambridge 2004: Cambridge University Press, 74-90, 89-90.

- 13Buchan, Mark: The Limits of Heroism. Homer and the Ethics of Reading. Ann Harbor 2004: University of Michigan Press.

- 14Segal, Charles P.: “Kleos and its Ironies in the Odyssey”. In: Antiquité Classique 52 (1983), 22-47.

- 15Martin, Richard P.: The Language of Heroes. Speech and Performance in the Iliad. Ithaca 1989: Cornell University Press.

- 16Vandiver, Elizabeth: Stand in the Trench, Achilles. Classical Receptions in British Poetry of the Great War. Oxford 2010: Oxford University Press.

- 17Zilling, Henrike M.: Jesus als Held. Odysseus und Herakles als Vorbilder christlicher Heldentypologie. Paderborn 2000: Schöningh.

- 18De Jong, Irene: Narrators and Focalizers. The Presentation of the Story in the Iliad. Amsterdam 1987: Grüner.

- 19Grethlein, Jonas: “Homer and Heroic History”. In: Marincola, John / Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd / Maciver, Calum A. (Eds.): Greek Notions of the Past in the Archaic and Classical Eras. History without Historians. Edinburgh 2012: Edinburgh University Press, 14-36.

- 20Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. Zürich 1981–1994: Artemis.

- 21Kemp-Lindemann, Dagmar: Darstellungen des Achilleus in griechischer und römischer Kunst. Frankfurt a. M. 1975: Lang; Balensiefen, Lilian: “Achills verwundbare Ferse. Zum Wandel der Gestalt des Achill in nacharchaischer Zeit”. In: Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 111 (1996), 75-103; see also Latacz, Joachim: Achilleus. Wandlungen eines europäischen Heldenbildes. Stuttgart 1995: Teubner; regarding Achilles see also endnotes 49 and 50.

- 22Brommer, Frank: Odysseus. Die Taten und Leiden des Helden in antiker Kunst und Literatur. Darmstadt 1983: WBG; Andreae, Bernhard (Ed.): Odysseus. Mythos und Erinnerung. Mainz 1999: Philipp von Zabern; see also von den Hoff, Ralf: “Odysseus in der antiken Bildkunst”. In: Gehrke, Hans-Joachim / Kirschkowski, Mirko (Eds.): Odysseus. Irrfahrten durch die Jahrhunderte. Freiburg i. Br. 2009: Rombach, 39-64.

- 23Laimou, Anna A.: “Aίας o Tελαμώνιoς στην αρχαία ελληνική και πρώιμη ρωμαϊκή εικoνoγραφία”. In: Archaiologiki Ephemeris 138 (1999), 15-40.

- 24Dardenay, Alexandra: Les mythes fondateurs de Rome. Images et politique dans l’Occident romain. Paris 2010: Picard; Dardenay, Alexandra: Images des fondateurs. D’Énée à Romulus. Pessac 2012: Ausonius.

- 25Ilias: Friis Johansen, Knud: The Iliad in Early Greek Art. Kopenhagen 1967: Munksgaard. – Odyssee: Touchefeu-Meynier, Odette: Thèmes odysséens dans l’art antique. Paris 1968: Boccard; Buitron-Oliver, Diana: The Odyssey and Ancient Art. An Epic in Word and Image. Annandale-on-Hudson 1992: E. C. Blum Art Institute. – redarding further Troy myths: Papadakis, Manuela: Ilias- und Iliupersisdarstellungen auf frühen rotfigurigen Vasen. Frankfurt a. M. 1994: Lang; Anderson, Michael J.: The Fall of Troy in Early Greek Poetry and Art. Oxford 1997: Clarendon; Lowenstam, Steven: As Witnessed by Images. The Trojan War Tradition in Greek and Etruscan Art. Baltimore 2008: Johns Hopkins University Press; Carpenter, Thomas H.: “The Trojan War in Early Greek Art”. In: Fantuzzi, Marco / Tsingalis, Christos (Eds.): The Greek Epic Cycle and its Ancient Reception. A Companion. Cambridge 2015: Cambridge University Press, 178-195.

- 26Latacz, Joachim: Homer. Der Mythos von Troia in Dichtung und Kunst. München 2008: Hirmer; Kunze, Christian: “Homeric Themes in Greek and Roman Sculpture”. In: Walter Karydi, Elena (Ed.): Mυθoι, κειμενα, εικoνες. Oμηρικα επη και αρχαια ελληνικη τεχην / Myths, Texts, Images. Homeric Epics and Ancient Greek Art. Ithaka 2010: Kentro Odyssiakon Spidon, 279-303; Junker, Klaus: “Ilias, Odyssee und die Bildenden Künste”. In: Rengakos, Antonios / Zimmermann, Bernhard (Eds.): Homer-Handbuch. Leben – Werk – Wirkung. Stuttgart 2011: Metzler, 395-410; see also Behr, Hans-Joachim (Ed.): Troia – Traum und Wirklichkeit. Ein Mythos in Geschichte und Rezeption. Braunschweig 2003: Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum.

- 27See, for example Shapiro, Harvey A.: Myth into Art. Poet and Painter in Classical Greece. London 1994: Routledge; Giuliani, Luca: Bild und Mythos. Geschichte der Bilderzählung in der griechischen Kunst. München 2003: Beck.

- 28In summary: Junker, Klaus: “Zur Bedeutung der frühesten Mythenbilder”. In: Schmidt, Stefan / Oakley, John H. (Eds.): Hermeneutik der Bilder. Beiträge zur Ikonographie und Interpretation griechischer Vasenmalerei. München 2009: Beck, 65-76.

- 29Schweitzer, Bernhard: Herakles. Aufsätze zur griechischen Religions- und Sagengeschichte. Tübingen 1922: Mohr; Hampe, Roland: Frühe griechische Sagenbilder in Böotien. Athen 1936: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut.

- 30Most recently Sforza, Ilaria: “Gli Attorioni Molioni e la categoria del ‘doppio naturale’: Omero, il mito e le immagini”. In: Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia 7 (2002), 297-320; Dahm, Murray K.: “Not Twins at All. The Agora Oinochoe Reinterpreted”. In: Hesperia 76 (2007), 717-730.

- 31Ahlberg, Gudrun: Fighting on Land and Sea in Greek Geometric Art. Stockholm 1971: Svenska Insitutet i Athen; Ahlberg, Gudrun: Prothesis and Ekphora in Greek Geometric Art. Göteborg 1971: Åström.

- 32Webster, Thomas B. L.: “Homer and Attic Geometric Vases”. In: Annual of the British School at Athens 50 (1955), 38-50.

- 33See however: Hurwirt, Jeffrey M.: “The Dipylon Shield once more”. In: Classical Antiquity 4 (1985) 121-126; Giuliani, Luca: “Myth as past? On the Temporal Aspect of Greek Depictions of Legend”. In: Foxhall, Lin et al. (Eds.): Intentional History. Spinning Time in Ancient Greece. Stuttgart 2010: Steiner, 35-56.

- 34Friis Johansen, Karsten: Ajas und Hektor. Ein vorhomerisches Heldenlied? Kopenhagen 1961: Munksgaard; Friis Johansen: “Iliad”, 1967; Coldstream, John N.: Geometric Greece. London 1977: Methuen, 352-356; concerning the jug in Munich see already: Kirk, Geoffrey: “Ships on Geometric Vases”. In: Annual of the British School in Athens 44 (1949), 93-153; Brunnsåker, Sture: “The Pithecusean Shipwreck. A Study of a Late Geometric Picture and Some Basic Aesthetic Concepts of the Geometric Figure-style”. In: Opuscula Romana 4 (1962), 165-242; most recently Giuliani: “Bild und Mythos”, 2003, 73-75; Hurwit, Jeffrey M.: “The Shipwreck of Odysseus. Strong and Weak Imagery in Late Geometric Art”. In: American Journal of Archaeology 115 (2011), 1-18.

- 35Fittschen, Klaus: Untersuchungen zum Beginn der Sagendarstellungen bei den Griechen. Berlin 1969: Hessling; Carter, John: “The Beginnings of Narrative Art in the Geometric Period”. In: Annual of the British School in Athens 67 (1972), 25-58; see also Ahlberg-Cornell, Gudrun: Myth and Epos in Early Greek Art. Jonserd 1992: Åström.

- 36Snodgrass, Anthony: Homer and the Artists. Text and Picture in Early Greek Art. Cambridge 1998: Cambridge University Press, with a review by Luca Giuliani in: Gnomon 73 (2001) 428-433; regarding the early reception of Homer in images cf. already: Kannicht, Richard: “Dichtung und Bildkunst. Die Rezeption der Troja-Epik in den frühgriechischen Sagenbildern”. In: Brunner, Helmut (Ed.): Wort und Bild. München 1979: Fink, 279-296; Kannicht, Richard: “Poetry and Art. Homer and the Monuments Afresh”. In: Classical Antiquity 1 (1982), 70-86; Cook, Robert M.: “Art and Epic in Archaic Greece”. In: Bulletin antieke beschaving 58 (1983), 1-6.

- 37Giuliani: “Bild und Mythos”, 2003.

- 38Langdon, Susan: Art and Identity in Dark Age Greece, 1100–700 B.C.E. Cambridge 2008: Cambridge University Press (quote p. 4).

- 39A comprehensive overview is also provided by: Schefold, Karl: Frühgriechische Sagenbilder. München 1964: Hirmer; Schefold, Karl: Götter- und Heldensagen der Griechen in der spätarchaischen Kunst. München 1978: Hirmer; Schefold, Karl / Jung, Franz: Die Sagen von den Argonauten, von Theben und Troia in der klassischen und hellenistischen Kunst. München 1989: Hirmer; Schefold 1993; Schefold, Karl: Götter- und Heldensagen der Griechen in der früh- und hocharchaischen Kunst. München 1993: Hirmer.

- 40Cf. the works of Tonio Hölscher, e.g. Hölscher, Tonio: Aus der Frühzeit der Griechen. Räume – Körper – Mythen. Stuttgart 1998: Teubner; Hölscher, Tonio: “Myths, Images, and the Typology of Identities in Early Greek Art”. In: Gruen, Erich S. (Ed.): Cultural Identity in the Ancient Mediterranean. Los Angeles 2011: Getty Research Institute, 47-65; see also Giuliani, Luca: “Mythen-versus Lebensbilder? Vom begrenzten Gebrauchswert einer beliebten Opposition”. In: Dally, Ortwin et al. (Eds.): Medien der Geschichte. Antikes Griechenland und Rom. Berlin 2014: de Gruyter, 204-226.

- 41Junker, Klaus: Pseudo-Homerica. Kunst und Epos im spätarchaischen Athen. Berlin 2003: de Gruyter.

- 42Sinn, Ulrich: Die homerischen Becher. Hellenistische Reliefkeramik aus Makedonien. Berlin 1979: Mann; Giuliani: “Bild und Mythos”, 2003, 263-280.

- 43Valenzuela Montenegro, Nina: Die Tabulae Iliacae. Mythos und Geschichte im Spiegel einer Gruppe frühkaiserzeitlicher Miniaturreliefs. Berlin 2002: dissertation.de; Squire, Michael: The Iliad in a Nutshell. Visualizing Epic on the Tabulae Iliacae. Oxford 2011: Oxford University Press.

- 44Andreae, Bernhard: Odysseus. Archäologie des europäischen Menschenbildes. Frankfurt a. M. 1982: Societaets-Verlag; Andreae, Bernhard: Praetorium speluncae. Tiberius und Ovid in Sperlonga. Stuttgart 1994: Steiner; Himmelmann, Nikolaus: Sperlonga. Die homerischen Gruppen und ihre Bildquellen. Opladen 1995: Westdeutscher Verlag; de Grummond, Nancy / Ridgeway, Brunilde S.: From Pergamon to Sperlonga. Sculpture and Context. Berkeley 2000: University of California Press; vgl. zudem Kunze, Christian: “Zur Datierung des Laokoon und der Skyllagruppe aus Sperlonga”. In: Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 111 (1996), 139-223.

- 45Biering, Ralf: Die Odysseefresken vom Esquilin. München 1994: Biering & Brinkmann.

- 46Moraw, Susanne: “Odysseus”. In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum, vol. 26. Stuttgart 2015: Hiersemann, 76-92; Moraw, Susanne: “Vom männlichen Bestehen einer Gefahr zur Ideologie der totalen Vernichtung. Scylla and the Sirens from Homer to Herrad von Hohenburg”. In: Visual Past 2.1 (2015), 89-135.

- 47Cf. von den Hoff, Ralf: “Odysseus. An Epic Hero with a Human Face”. In: Albersmeier, Susanne (Ed.): Heroes. Mortals and Myths in Ancient Greece. Baltimore 2009: Walters Art Museum, 57-65.

- 48Spieß, Angela B.: Der Kriegerabschied auf attischen Vasen der archaischen Zeit. Frankfurt a. M. 1992: Lang; Ellinghaus, Christian: Aristokratische Leitbilder – demokratische Leitbilder. Kampfdarstellungen auf athenischen Vasen in archaischer und frühklassischer Zeit. Münster 1997: Scriptorium; Recke, Matthias: Gewalt und Leid. Das Bild des Krieges bei den Athenern im 6. und 5. Jh. v. Chr. Istanbul 2002: Ege Yayınları.

- 49von den Hoff, Ralf: “‘Achill, das Vieh’? Zur Problematisierung transgressiver Gewalt in klassischen Vasenbildern”. In: Fischer, Günter / Moraw, Susanne (Eds.): Die andere Seite der Klassik. Gewalt im 5. und 4. Jahrhundert v. Chr. Stuttgart 2005: Steiner, 225-246; e.g. on an Attic hydria, c. 520/10 BC, in Boston, Museum of Fine Arts Inv. 63.473. Online at: https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153447/ (accessed on 22.04.2022); concerning images of violence cf. Blome, Peter: “Das Schreckliche im Bild”. In: Graf, Fritz (Ed.): Ansichten griechischer Rituale. Geburtstags-Symposium für Walter Burkert. Stuttgart 1998: Steiner, 72-95; Muth, Susanne: Gewalt im Bild. das Phänomen der medialen Gewalt im Athen des 6. und 5. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. Berlin 2008: de Gruyter, 93-133; Giuliani, Luca: “Helden-Hybris”. In: von den Hoff, Ralf / Meyer, Marion (Eds.): Helden wie sie. Übermensch – Vorbild – Kultfigur in der griechischen Antike. Freiburg i. Br. 2009: Rombach: 193-214.

- 50Giuliani, Luca: “Kriegers Tischsitten, oder die Grenzen der Menschlichkeit. Achill als Problemfigur”. In: Hölkeskamp, Karl Joachim et al. (Eds.): Sinn (in) der Antike. Orientierungssysteme, Leitbilder und Wertkonzepte im Altertum. Mainz 2003: Philipp von Zabern, 135-161; cf. the depiction on the skyphos of the ‘Brygos Painter’, c. 490 BC, in Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum Inv. IV 3710. Online at https://www.khm.at/objektdb/detail/56696/ (accessed on 01.09.2018).

- 51Himmelmann, Nikolaus: Der ausruhende Herakles. Paderborn 2009: Schöningh, 88-121.

- 52Junker: “Pseudo-Homerica”, 2003, 2-8; on this drinking bowl see Dorka Moreno, Martin: “Achilles, Patroklos and Herakles. Conceptions of kλέος on the So-Called Sosias Cup”. In: Helden. Heroes. Héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen, Special Issue 2 (2016), 17-25. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2016/QMR/04.

- 53Mommsen, Heide: “Achill und Aias pflichtvergessen?” In: Cahn, Herbert Adolph et al. (Eds.): Tainia. Roland Hampe zum 70. Geburtstag. Mainz 1980: Philipp von Zabern, 139-152; Woodford, Susan: “Ajax and Achilles Playing a Game on an Olpe in Oxford”. In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies 102 (1982), 173-185; Junker: “Pseudo-Homeric”, 2003, 8-16.

- 54Kunze, Christian: “Dialog statt Gewalt. Neue Erzählperspektiven in der frühklassischen Vasenmalerei”. In: Fischer, Günther / Moraw, Susanne (Eds.): Die andere Seite der Klassik. Gewalt im 5. und 4. Jahrhundert v. Chr. Stuttgart 2005: Steiner, 45-71.

- 55Dorka Moreno: “Achilles, Patroklos and Herakles”, 2016.

- 56Snodgrass: “Homer and the Artists”, 1998, 141.

- 57Penelope: Hölscher, Tonio: “Penelope für Persepolis, oder: Wie man einen Krieg gegen den Erzfeind beendet”. In: Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 126 (2011), 33-76; see also “396 Penelope”. In: iDAIObjects/Arachne. Online at: http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/typus/396 (accessed on 01.09.2018) – Diomedes: Landwehr, Christa: “Juba II. als Diomedes?” In: Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 107 (1992), 103-124; see also “170 Diomedes Cuma – München”. In: iDAIObjects/Arachne. Online at: http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/typus/170 (accessed on 09.01.2018), and Hildebrandt, Frank: “Diomedes, tauglich für die römische Herrschaftsikonogaphie?” In: Ganschow, Thomas (Ed.): Otium. Festschrift für Volker Michael Strocka. Remshalden 2005: Greiner, 149-153.

- 58Most recently with older literature: Vollmer, Cornelius: “Eine Allegorie der Demokratie? Zur Benennung des polykletischen Doryphoros”. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. Athenische Abteilung 129–130 (2014–15), 125-146; besides Achilles, Orestes or Polydeukes are sometimes recognised in the ‘Doryphoros’; see also „191 Doryphoros“. In: iDAIObjects/Arachne. Online at: http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/typus/191 (accessed on 01.09.2018). – A bronze replica of the Doryphoros served as a memorial to the fallen of the First World War at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich from 1920/21: Schneider, Rolf M.: “Polyklet: Forschungsbericht und Antikenrezeption”. In: Beck, Hans et al. (Eds.): Polyklet. Der Bildhauer der griechischen Klassik. Mainz 1990: Philipp von Zabern, 485-494.

- 59Stewart, Andrew: Faces of Power. Alexander’s Image and Hellenistic Politics. Berkeley 1993: University of California Press, esp. 78-86; critical of the connections between Alexander and Achilles: Heckel, Waldemar: “Alexander, Achilles and Heracles. Between Myth and History”. In: Wheatley, Pat / Baynham, Elisabeth (Eds.): East and West in the World Empire of Alexander. Essays in Honor of Brian Bosworth. Oxford 2015: Oxford University Press, 21-34.

- 60Wrede, Henning: Consecratio in formam deorum. Vergöttlichte Privatpersonen in der römischen Kaiserzeit. Mainz 1981: Philipp von Zabern; Maderna, Caterina: Iuppiter, Diomedes und Merkur als Vorbilder für römische Bildnisstatuen. Heidelberg 1988: Verlag Archäologie und Geschichte; see also Hildebrandt: “Diomedes”, 2005.

- 61See endnote 43.

- 62Pasquino: Wünsche, Raimund: “Pasquino”. In: Münchner Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst 42 (1991), 7-38; with another designation: Weis, Anne: “The Pasquino Group and Sperlonga. Menelaos and Patroklos or Aeneas and Lausus (Aen. 10, 791-832)?” In: Στεφανoς. Studies in Honor of Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway. Philadelphia 1998: University Museum Publications, 255-286; see also “395 Pasquino-Gruppe”. In: iDAIObjects/Arachne. Online at: http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/typus/395 (accessed on 01.09.2018).

- 63Grassinger, Dagmar: “Die Achill-Penthesilea-Gruppe sowie die Pasquino-Gruppe und ihre Rezeption in der Kaiserzeit”. In: Hellenistische Gruppen. Gedenkschrift für Andreas Linfert. Mainz 1999: Philipp von Zabern, 323-330; see also iDAIObjects/Arachne. Online at: http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/typus/753; http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/typus/754 (accessed on 01.09.2018).

- 64See endnote 44.

- 65Dardenay: “Les mythes fondateurs de Rome”, 2010; Dardenay: “Images des fondateurs”, 2012.

- 66Münzen: Pause-Dreyer, Ursula: Die Heroen des Trojanischen Krieges auf griechischen Münzen. München 1975: Universität München; Lindner, Ruth: Mythos und Identität. Studien zur Selbstdarstellung kleinasiatischer Städte in der römischen Kaiserzeit. Stuttgart 1994: Steiner; Krumme, Michael: Römische Sagen in der antiken Münzprägung. Marburg 1995: Hitzeroth; Böhm, Stephanie: Die Münzen der Römischen Republik und ihre Bildquellen. Mainz 1997: Philipp von Zabern. – Funerary buildings: Lorenz, Susanne M.: Untersuchungen zum römischen Gründungsmythos in der Sepulkralkunst. Dissertation Heidelberg 2001: Universität Heidelberg. Online at: https://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/volltextserver/20642/1/Diss_Lorenz_PDFA.pdf (accessed on 01.09.2018).

- 67Koortbojian, Michael: Myth, Meaning, and Memory on Roman Sarcophagi. Berkeley 1995: University of California Press; Rogge, Sabine: Die attischen Sarkophage 1. Achill und Hippolytos. Berlin 1995: Mann; Zanker, Paul / Ewald, Björn (Eds.): Mit Mythen leben. Die Bilderwelt der römischen Sarkophage. München 2004: Hirmer; see also: Moraw, Susanne: “Odysseus in der Sepulkralkunst der Stadt Rom. Eine Allegorie für die menschliche Seele?” In: Eich, Armin et al. (Eds.): Das dritte Jahrhundert. Kontinuitäten, Brüche, Übergänge. Stuttgart 2017: Steiner, 123-146, and the following note.

- 68Ewald, Björn C.: “Das Sirenenabenteuer des Odysseus, ein Tugendsymbol? Überlegungen zur Adaptabilität eines Mythos”. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. Römische Abteilung 105 (1998), 227-258; Moraw: “Vom männlichen Bestehen einer Gefahr”, 2015.

- 69Ghedini, Francesca: Il carro dei Musei Capitoloni. Epos e mito nella società tardo antica. Rom 2009: Quasar.

- 70Kaufmann-Heinimann, Annemarie / Furger, Alex R.: Der Silberschatz von Kaiseraugst. Augst 1984: Römermuseum, 225-307, catalogue no. 63 tab. 146-160; Hengel, Martin: Achilleus in Jerusalem. Eine spätantike Messingkanne mit Achilleus-Darstellungen aus Jerusalem. Heidelberg 1982: Winter.

- 71Bianchi-Bandinelli, Ranuccio: Hellenistic-Byzantine Miniatures of the Iliad. Ilias Ambrosiana. Olten 1955: Graf; Weitzmann, Kurt: Spätantike und frühchristliche Buchmalerei. München 1977: Prestel, 44-51.

- 72Moraw: “Vom männlichen Bestehen einer Gefahr”, 2015.

- 73For example Junker: “Pseudo-Homerica”, 2003; Hurwit: “Shipwreck of Odysseus”, 2011; von den Hoff, Ralf: “Vom Heros erzählen. Visuelle Strategien der Heldennarration im antiken Griechenland”. In: Heinemann, Alexander et al. (Eds.): Image – Narration – Context. Visual Narration in Culutures and Societies of the Old World. Heidelberg 2019: Propylaeum. Online at: https://books.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/propylaeum/series/info/favis (accessed on 07.09.2018).

- 74Neils, Jennifer: “Hera, Paestum, and the Cleveland Painter”. In: Marconi, Clemente (Ed.): Greek Vases. Images, Contexts and Controversies. Leiden 2004, Brill, 78-81; on ‘mythicising’ antiquaria see also: Schäfer, Thomas: Andres Agathoi. Studien zum Realitätsgehalt der Bewaffnung attischer Krieger auf Denkmälern klassischer Zeit. München 1998: tuduv; Giuliani, Luca: “Myth as past? On the temporal aspect of Greek depictions of legend”. In: Foxhall, Lin et al. (Eds.): Intentional History. Spinning Time in Ancient Greece. Stuttgart 2010: Steiner, 35-56.

- 75Thus the Attic heroes Demophon and Akamas often appeared in Homeric scenes in Athens in the 5th century BC (for literature on this see note 25). In the Troad, Homeric images were used as a means of establishing identity: Lindner: “Mythos und Identität”, 1994; Özgünel, Coşkun: “Das Heiligtum des Apollon Smintheus und die Ilias”. In: Studia Troica 13 (2003), 261-291. – On such phenomena see also Erskine, Andrew: Troy between Greece and Rome. Local Tradition and Imperial Power. Oxford 2001: Oxford University Press.

5. Selected literature

- Ahlberg-Cornell, Gudrun: Myth and Epos in Early Greek Art. Jonserd 1992: Åström.

- Althoff, Jochen: “Die homerischen Epen als Heldenepik”. In: Meisig, Konrad (Ed.): Ruhm und Unsterblichkeit. Heldenepik im Kulturvergleich. Wiesbaden 2010: Harrassowitz, 13-32.

- Bianchi-Bandinelli, Ranuccio: Hellenistic-Byzantine Miniatures of the Iliad. Ilias Ambrosiana. Olten 1955: Graf.

- Buchan, Mark: The Limits of Heroism. Homer and the Ethics of Reading. Ann Harbor 2004: University of Michigan Press.

- Buitron-Oliver, Diana: The Odyssey and Ancient Art. An Epic in Word and Image. Annandale-on-Hudson 1992: E. C. Blum Art Institute.

- Carpenter, Thomas H.: “The Trojan War in Early Greek Art”. In: Fantuzzi, Marco / Tsingalis, Christos (Eds.): The Greek epic cycle and its ancient reception. A companion. Cambridge 2015: Cambridge University Press, 178-195.

- Clarke, Michael: “Manhood and Heroism”. In: Fowler, Robert (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to Homer. Cambridge 2004: Cambridge University Press, 74-90.

- Fittschen, Klaus: Untersuchungen zum Beginn der Sagendarstellungen bei den Griechen. Berlin 1969: Hessling.

- Friis Johansen, Knud: The Iliad in Early Greek Art. Kopenhagen 1967: Munksgaard.

- Himmelmann, Nikolaus: Sperlonga. Die homerischen Gruppen und ihre Bildquellen. Opladen 1995: Westdeutscher Verlag.

- Horn, Fabian: Held und Heldentum bei Homer. Das homerische Heldenkonzept und seine poetische Verwendung. Tübingen 2014: Narr.

- Hurwit, Jeffrey M.: “The Shipwreck of Odysseus. Strong and Weak Imagery in Late Geometric Art”. In: American Journal of Archaeology 115 (2011), 1-18.

- Junker, Klaus: Pseudo-Homerica. Kunst und Epos im spätarchaischen Athen. Berlin 2003: de Gruyter.

- Junker, Klaus: “Ilias, Odyssee und die Bildenden Künste”. In: Rengakos, Antonios / Zimmermann, Bernhard (Eds.): Homer-Handbuch. Leben – Werk – Wirkung. Stuttgart 2011: Metzler, 395-410.

- Kannicht, Richard: “Dichtung und Bildkunst. Die Rezeption der Troja-Epik in den frühgriechischen Sagenbildern”. In: Brunner, Helmut (Ed.): Wort und Bild. München 1979: Fink, 279-296.

- Kannicht, Richard: “Poetry and Art. Homer and the Monuments Afresh”. In: Classical Antiquity 1 (1982), 70-86.

- Kunze, Christian: “Homeric Themes in Greek and Roman Sculpture”. In: Walter Karydi, Elena (Ed.): Mυθoι, κειμενα, εικoνες. Oμηρικα επη και αρχαια ελληνικη τεχην / Myths, Texts, Images. Homeric Epics and Ancient Greek Art. Ithaka 2010: Kentro Odyssiakon Spidon, 279-303.

- Jones, Christopher P.: “New Heroes in Antiquity”. In: Revealing Antiquity 18 (2011). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Latacz, Joachim: Homer. Der Mythos von Troia in Dichtung und Kunst. München 2008: Hirmer.

- Lowenstam, Steven: As Witnessed by Images. The Trojan War Tradition in Greek and Etruscan Art. Baltimore 2008: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Martin, Richard P.: The Language of Heroes. Speech and Performance in the Iliad. Ithaca 1989: Cornell University Press.

- Nagy, Gregory: The Best of the Achaeans. Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry, 2nd ed. Baltimore 1999: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Nagy, Gregory: “The Epic Hero”. In: Foley, John M. (Ed.): A Companion to Ancient Epic. Malden, Mass. 2005: Blackwell, 71-89.

- Pause-Dreyer, Ursula: Die Heroen des Trojanischen Krieges auf griechischen Münzen. München 1975: Universität München.

- Schefold, Karl: Götter- und Heldensagen der Griechen in der spätarchaischen Kunst. München 1978: Hirmer.

- Schefold, Karl: Götter- und Heldensagen der Griechen in der früh- und hocharchaischen Kunst. München 1993: Hirmer.

- Schein, Seth L.: The Mortal Hero. An Introduction to Homer’s Iliad. Berkeley 1984: University of California Press.

- Schefold, Karl / Jung, Franz (Eds.): Die Sagen von den Argonauten, von Theben und Troia in der klassischen und hellenistischen Kunst. München 1989: Hirmer.

- Segal, Charles P.: “Kleos and its Ironies in the Odyssey”. In: Antiquité Classique 52 (1983), 22-47.

- Shapiro, Harvey A.: Myth into Art. Poet and Painter in Classical Greece. London 1994: Routledge.

- Sinn, Ulrich: Die homerischen Becher. Hellenistische Reliefkeramik aus Makedonien. Berlin 1979: Mann.

- Snodgrass, Anthony: Homer and the Artists. Text and Picture in Early Greek Art. Cambridge 1998: Cambridge University Press.

- Squire, Michael: The Iliad in a Nutshell. Visualizing Epic on the Tabulae Iliacae. Oxford 2011: Oxford University Press.

- Touchefeu-Meynier, Odette: Thèmes odysséens dans l’art antique. Paris 1968: Boccard.

- Webster, Thomas B. L.: “Homer and Attic Geometric Vases”. In: Annual of the British School at Athens 50 (1955), 38-50.

6. List of images

- Aias with the body of Achilles or Menelaus with the body of Patroclus, Roman copy of a Hellenistic statuary group (with modern additions). Marble. Florence, Loggia dei Lanzi.Lizenz: Creative Commons BY 2.5 Generic

- 1Schiffbruch, attisch-geometrische Kanne, spätes 8. Jh. v. Chr. Ton, Höhe 21,5 cm. München, Antikensammlung, Inv.-Nr. 8696.Quelle: Foto der Staatlichen Antikensammlungen MünchenLizenz: Zitat nach § 51 UrhG

- 2Blendung des Polyphem (Odyssee 9, 166-566), attische Halsamphora, gegen 670 v. Chr. Ton. Eleusis, Archäologisches Museum Inv. 2630.Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0

- 3Zweikampf des Menelaos und Paris (Ilias 3, 250-461), attisch-rotfigurige Trinkschale, gegen 490 v. Chr. Ton. Paris, Musée du Louvre Inv. G 115.Quelle: User:Jastrow / Wikimedia CommonsLizenz: Public Domain

- 4Achilleus erhält von Thetis die Waffen des Hephaistos (Ilias 19, 1-36), attisch-schwarzfigurige Hydria, gegen 570/60 v. Chr. Ton. Paris, Musée du Louvre Inv. E 869.Quelle: User:Jastrow / Wikimedia CommonsLizenz: Public Domain

- 5Achill verbindet Patroklos, attisch-rotfigurige Trinkschale des Sosias, um 500/490 v. Chr. Ton. Berlin, Staatliche Museen/SMPK – Antikensammlung Inv. F 2278.Lizenz: Public Domain

- 6Aias und Achill beim Brettspiel, attisch-schwarzfigurige Bauchamphora des Exekias, gegen 530 v. Chr. Ton. Rom, Musei Vaticani Inv. 16757.Lizenz: Public Domain

- 7Diomedes, römische Kopie einer Statue des späteren 5. Jhs. v. Chr. (Palladion fehlt). Marmor. München, Glyptothek Inv. 304.

- 8‚Tabula Iliaca‘ mit Reliefdarstellungen der Ilias, 1. Jh. v./n. Chr. Marmor, Höhe 25 cm. Rom, Musei Capitolini Inv. 316.Quelle: User:Jastrow / Wikimedia CommonsLizenz: Public Domain

- 9Aias mit dem Leichnam Achills oder Menelaos mit dem Leichnam des Patroklos, römische Kopie einer hellenistischen Statuengruppe (mit modernen Ergänzungen). Marmor. Florenz, Loggia dei Lanzi.Lizenz: Creative Commons BY 2.5 Generic

- 10Skylla greift das Schiff des Odysseus an (Odyssee 12, 222-259), späthellenistische Statuengruppe (Ende 1. Jh. v. Chr.) aus der Villa von Sperlonga. Marmor. Museo Archaelogico di Sperlonga.Quelle: steveilott / FlickrLizenz: Creative Commons BY 2.0

- 11Odysseus und seine Gefährten blenden Polyphem (Odyssee 9, 166-566), Rekonstruktion einer späthellenistischen Statuengruppe (Ende 1. Jh. v. Chr.) aus der Villa von Sperlonga (Rekonstruktion). Gips (Abgüsse). Museo Archaeologico di Sperlonga.Quelle: Carole Raddato / FlickrLizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 2.0

- 12Platte mit Reliefdarstellungen aus dem Leben des Achill, um 350 n. Chr. Silber, Durchmesser 53 cm. Augst, Römermuseum Inv. 62.1.

- 13Odysseus und Diomedes fangen Dolon (Ilias 10), Illustration in der Ilias Ambrosiana, 5. Jh. n. Chr. Mailand, Bibliotheca Ambrosiana Cod. F 205 inf. Nr. 34.Quelle: Dsmdgold / Wikimedia CommonsLizenz: Public Domain