- Version 1.0

- publiziert am 7. November 2022

Inhalt

1. Introduction

Enduring is an act that first can be defined in negative terms: to endure means not to quit, be it during a marathon, on I’m a Celebrity … Get Me Out of Here!, while on a diet or when preparing for exams. If enduring can thus be considered part of our everyday, it may be surprising to examine this “Keep it up” as an heroic act. And still we encounter figures who are portrayed as ⟶heroes precisely because they do not quit. For instance, we think of Captain Robert Falcon Scott and his gruelling, indeed fatal, expedition to the South Pole; of Odysseus, who tirelessly continues his wanderings imposed on him by the gods until he finally reaches home in Ithaca; or of Nelson Mandela, whose struggle against South Africa’s apartheid regime can be told as a story of yearslong defiance and heroic endurance. Despite the evidence for a close link between enduring and heroism, scholarship has dealt with this question only rudimentarily. One pertinent study is Nicolas Detering’s article on ‘heroic fatalism’, which not only pieces together the elements of the concept systematically, it also highlights actualisations thereof in German literature between 1900 and 1945.1Detering, Nicolas: “Heroischer Fatalismus. Denkfiguren des ‘Durchhaltens’ von Nietzsche bis Seghers.” In: Literaturwissenschaftliches Jahrbuch, Neue Folge 60 (2019), 317-339. Key ideas of this article, especially with regards to the definition of ‘durchhalten’ (to endure), are due to Detering’s work as well as a workshop on this topic organised by the Sonderforschungsbereich 948/Project D6 on 19 January 2018. Lothar Bluhm’s conceptual history Auf verlorenem Posten (2012) must also be mentioned, in which he traces the trope’s line of development from the Baroque period into the 21st century. In some chapters, he illustrates the link between ‘enduring in one’s last stand’ and heroism.2Bluhm, Lothar: Auf verlorenem Posten. Ein Streifzug durch die Geschichte eines Sprachbildes. Trier 2012: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier.

2. Definition

In the following, the ‘will to endure’ is understood to mean a subject’s disposition (i) to resist the pressing physical or mental need in strenuous circumstances to give up or comply and (ii) to carry on in that given situation. That means while the ‘will to endure’ focuses on willingness and attitude, ‘enduring’ per se describes the act that follows from it. Using Max Weber’s broad notion of action, ‘enduring’ (the German term used by Weber is ‘Dulden’) can be thought of as active, lasting action whenever a subjective meaning is associated with it, i.e. the action is intentional and not coincidental.3Cf. Weber, Max: Economy and Society. A New Translation. Ed. and transl. by Keith Tribe. Cambridge, Massachusetts 2019: Harvard University Press, 103. (For the original German text cf. Weber, Max: Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Grundriss der verstehenden Soziologie. Studienausgabe hg. von Johannes Winckelmann. Erster Halbband. Köln/Berlin 1964: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 16.) For a more extensive look at Weber’s concept of ‘action’ and its usefulness for a heuristic of the heroic, cf. Aurnhammer, Achim / Klessinger, Hanna: “Was macht Schillers Wilhelm Tell zum Helden? Eine deskriptive Heuristik heroischen Handelns.” In: Jahrbuch der deutschen Schillergesellschaft 62 (2018), 127-149, 130-132. In this sense, ‘enduring’ cannot be regarded as the postponing of a deed to be delivered on at a later time, but as the deed itself. When ‘enduring’, the subject’s options and alternatives are considerably limited. The subject has neither the possibility of effecting change on their present situation, nor can they reach their goal in any other way. Even as different as the circumstances may be that necessitate an act of endurance4Detering: “Heroischer Fatalismus”, 2019, 321, lists the resilience of an antagonistic opponent, adverse weather conditions and time that simply never wants to end. That list bears amending with physical overexertion – in particular with regard to sport as a central domain of ‘enduring’ – but also with pressure at a social or political level, like Mandela’s example shows., they all have in common that they force the subject to the brink of mental or physical exhaustion and that they steadily intensify the need to give up or comply. This suffering constitutes the prerequisite after all to be able to speak of a ‘will to endure’ and ‘enduring’. The willingness to accept and bear the privations and exhaustion in turn requires mental fortitude, emotional regulation, self-discipline and a willingness to make sacrifices. In this respect, notions of the ‘will to endure’ tie in with older models such as stoicism (‘apathy’), Epicureanism (‘ataraxia’) or asceticism, with which they share the virtues of self-discipline, self-control and self-mastery.5The parallels primarily to stoicism are also drawn by Detering: “Heroischer Fatalismus”, 2019, 321. Enduring is therefore a trial against oneself, against the urge to capitulate and resign.

Furthermore, enduring constitutes a lasting state that is also orientated towards the final outcome. A goal that is being worked towards or even awaited is anticipated, but at the same time has become so distant that enduring extends over a prolonged period of time. The goal is present only in a prospective sense. The finality of the act of enduring promises in this context not just the end of the austere situation, but also overwrites it with meaning and provides the act of enduring with its legitimacy.6Finality as a central component of ‘enduring’ is also discussed by Detering: “Heroischer Fatalismus”, 2019, 320-321, but without establishing a connection to the attribution of meaning and legitimisation. Enduring therefore takes place not just for the sake of itself, but for a purpose. The success, however, is attributed little to no meaning since the focus is on the confrontation with oneself. In this respect, there can be a different degree of hope for an end to the act of enduring. In a nutshell, the will to endure can be described using the words of Ernst Bertram (1884–1957): a ‘Haltung des Dennoch’, an ‘attitude of nevertheless’.7Cf. Bluhm: Auf verlorenem Posten, 2012, 111-113, and Detering: “Heroischer Fatalismus”, 2019, 324. The phrase expresses the adversity of the circumstances and the arduousness of the situation on the one hand, and on the other hand the inner willingness to stand firm and remain composed despite of, or precisely because of, that adversity and arduousness. This is true both for concrete situations of enduring that can be precisely located in space and time, such as in war and sport (see below), and for sociologically diagnostic positions. Hence, in the Weimar Republic, Ernst Bertram’s expression was seized on by Thomas Mann, Oswald Spengler and others, who repurposed it into an ideological-political concept that outlines a moral, fate-affirming attitude in the face of an impending (cultural, social, political, …) downfall. 8Regarding the popularity of this attitude in the Weimar Republic and the Nazi period, cf. Bluhm: Auf verlorenem Posten, 2012, 113-136; specifically regarding Thomas Mann, cf. Detering: “Heroischer Fatalismus”, 2019, 324-326. This attitude is invoked paradigmatically for instance in Gottfried Benn’s poem Dennoch die Schwerter halten (“Hold the swords in defiance” – 1933). It appeals for both a defiant affirmation of fate (‘amor fati’) and fortitude despite the awareness of an imminent demise, in addition to marking this conduct as heroic.

3. Heroization

Specific forms of heroic conduct that are not constrained to a one-time and brief ⟶heroic deed require the hero to have a considerable ‘will to endure’. In such cases, the act of ‘enduring’ takes the place of a single decisive heroic deed and becomes per se ⟶heroizable. The prerequisite for this is the ‘value-rational’ purpose (Max Weber) of the act of endurance, i.e. it must happen “through conscious belief in the unconditional and intrinsic value – whether this is understood as ethical, aesthetic, religious, or however construed – of a specific form of particular comportment purely for itself, unrelated to its outcome”.9Weber: Economy and Society, 2019, 103. This type of action must be differentiated from the ‘purposive-rational’, ‘affectual/emotional’ and ‘traditional’ types of action (cf. ibid.). The heroization potential of enduring certainly depends on different parameters; however, it does draw upon and modify the common typological characteristics of the heroic.10These typological characteristics are the result of discussions held at the Sonderforschungsbereich 948. They help in describing numerous different hero figures and their narratives. In the specific case, each of the characteristics can, but does not have to, mark the heroization or medialisation. Cf. also Tobias Schlechtriemen’s article on the ⟶Constitutive Processes of Heroic Figures. It is worth noting that these are always attributions that arise only through their representation in media (see below).

a) Agonality

The agonality of a heroic action is internalised in the case of an act of enduring. The agonality separates from the external factors and shifts to the subject’s struggle against oneself. The action, i.e. the withstanding the circumstances and the not-relenting, moves to the inside during the performance of that action. That which constitutes the decisive moment inwardly therefore appears to be a non-deed outwardly.

b) Agency

The situation that necessitates an act of endurance may be freely chosen or forced from without. The solely decisive factor is that the hero makes an affirmation of his own volition, meaning that a deliberately affirmative positioning on privation and exhaustion is played out. Only then can the suffering be redefined as a confident, ⟶self-empowered action.

c) Exceptionality

The situation that necessitates an act of endurance is an extreme situation that demands exceptional ⟶corporeal, but in particular mental strength and stamina from the hero. In this respect, he sets himself apart from the average masses, who are generally not capable of this feat.

d) Transgressivity (temporal)

In an act of endurance, the hero’s own physical and/or mental boundaries that he pushes and that compel him to rise above himself are of a temporal nature. It is the long duration of the situation of enduring that brings the hero to the verge of physical and/or mental exhaustion. In order not to succumb to the exhaustion, boundaries have to be crossed. The situation therefore represents a danger to the physical and psychological health of the hero, endangers his existence and can result in his death. This is the maximum expression of ⟶transgression.

4. Medialisation

In actual heroizations of acts of endurance, each of the attributions is expressed in a unique way. The internalisation of the agonality in the struggle against the hero’s own need to capitulate; a self-empowered, active affirmation of the inescapable situation; exceptional physical and mental capability and a transgressive rising-above-oneself – these all serve in different ways to have the act of endurance appear as a heroic act. As different as these attributions are, they nevertheless are all characterised by a particular interiority: as a trial of the hero’s own physical and mental commitment; as a confrontation with the boundaries that his own body sets; as a struggle against himself and as an affirmation of his own will.

a) Internalised agonality

Because of the aforementioned interiority, the heroization of enduring requires a noticeable medialisation effort. In that context, the heroic (re)presentation fulfils a dual function that tends to be contradictory: on the one hand, the internal processes are singled out and seemingly turned inside out, making them usable for the heroization and rendering the (re)presented action interpretable as an heroic act of endurance. On the other hand, the deheroizing tendencies that accompany interiority must be handled distinctly so that they do not prevent or interfere with the heroization. Possible textualisation strategies of such internal processes that a novel offers for instance include internal focalisation, character’s voice and thought presentation, all the way to stream of consciousness. The struggle against oneself – be it resisting the urgent desire to flee or, entirely to the contrary, to act; be it wrestling with one’s weaker self – can also be made visible in media using figures from the endurer’s entourage, who for instance comment on the action or, as the community of admirers, acknowledge it in wonder and encourage the hero in his action. In individual cases, that can even mean that these figures embody the hero’s internal antagonistic parties and needs, and in this way they express the options from which the endurer himself refrains.

b) Agency

The decisive aspect in this respect is that the agency of the enduring hero remains plausible even in the limiting, often disempowering space that he has to act, namely to decide whether to endure or, its opposite, to quit. Although the explosiveness of the heroic trial can be seen precisely when the act of enduring, as the hero’s only course of action, is portrayed as an important mission, the heroic act can thereby be semantically upended: in particular, when there are additional contextual conditions to the act of enduring, such as divine determinacy, a military assignment or rules of a competition, the hero can also be understood as one driven by outside forces whose decision-making is relegated to those forces, or he can be seen as a passive sufferer who merely submits to the adverse circumstances. Consequentially, it has been observed that situations that are actually disempowering because of their inescapability are reassessed as being positive and activating, for instance, by the attitude being emphasised more than the act itself.

c) Exceptionality

The heroic attribution of an exceptional physical and mental achievement presents a comparable tipping point. The rising-above-oneself in the clash with the boundaries that one’s own body sets can be portrayed as suffering, for instance through a depiction of a bleeding wound or a face contorted by pain. In terms of media, this is achieved through a special visibility, produced by the fine arts in particular, but also by mimetic and descriptive textualisation processes. The internal and fundamentally subjective experience of boundaries thus reveals itself to be a corporeal event – the suffering visibly certifies the heroic achievement. The heroizing (re)presentation therefore aims to provide a striking portrayal of the hero’s physical and psychological anguish because the quality and exceptionality of heroic enduring is measured against the pain suffered by the hero. However, this focus of the portrayal on the heroic body in turn generates deheroizing effects, for they leave the enduring hero seeming less an abstract, depersonalised projection figure and more a human out of flesh and blood. The suffering that on the one hand gives expression to the hero’s corporeal achievement with such affective power tends on the other hand to equate the hero with the audience. By dramatising the physical and psychological ordeal out of necessity, the heroization places the hero on a fine line: if his actions elicit primarily sympathy, his heroic act of endurance appears as mere suffering that leaves the exceptionality disappear in the all too human.

d) Finality and transgressivity

On a structural level, the emphasis on the lasting dimension turns the purpose into the culmination point of the action. For example, the mental and physical stamina associated with the heroic act of enduring can be portrayed in a way that experientially actualises the stamina for the audience in addition to making it comprehensible. Moreover, because of its finality, the heroic endurance narrative entails the enormous appreciation of a certain purpose or value that gives the act its meaning. This strong finality of the heroic act of enduring can also produce ambivalent effects on the audience. By presenting the goal in categorical unambiguity, the heroization calls upon the audience to take a position, in addition to posing the question whether the presented purpose can justify the greatly depriving act plausibly. The polarisation can therefore lead to the heroization of the act of endurance being perceived as unbelievable, appearing fanatical or becoming ridiculous.

5. Examples

5.1. The First World War

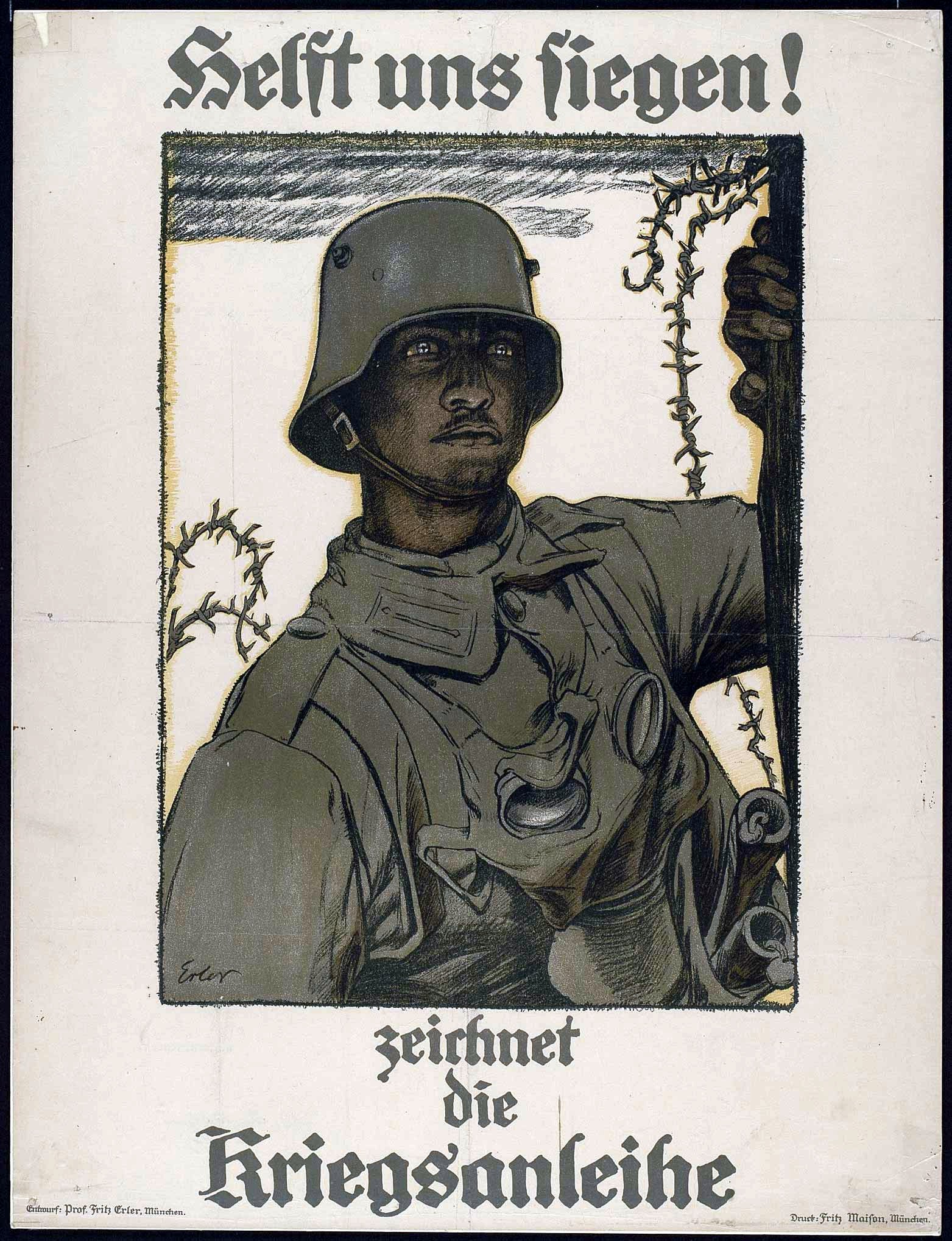

The First World War constitutes one of the gravest events that shaped discourses over heroic endurance. The deployment of such advanced technology as heavy artillery and the machine gun along with the construction of fortified trench networks for defence rendered the primacy of the offensive obsolete and stripped traditional heroic notions of their validity. Against the background of perpetual trench warfare on the Western front, which claimed horrendous numbers of casualties for only negligible territorial gains, ‘enduring’ evolved into a central catchword of the wartime propaganda of the warring states. Endurance rhetoric found expression primarily in the (war-affirming) newspapers, but was adopted by the soldiers themselves in their letters home.11Cf. Reimann, Aribert: Der große Krieg der Sprachen. Untersuchungen zur historischen Semantik in Deutschland und England zur Zeit des Ersten Weltkriegs. Essen 2000: Klartext, 28-48. On posters and postcards, the rhetoric was realised visually, showing idealised images of the ‘steely fighter’. Fritz Erler’s poster for the sixth war bond from spring 1917, “Man with the steel helmet before Verdun”, for instance shows a soldier in uniform wearing a steel helmet, carrying two hand grenades in his bag and with a gas mask around his neck. The war is made present through the barbed wire and simultaneously pushed into the background: the focus is on the soldier’s willpower and strength of nerve. There is a resolute look on his face; his eyes are glowing and looking into the distance. The (re)presented soldier unmistakably embodies the virtue of heroically enduring until the awaited victory.12Regarding Fritz Erler’s poster, cf. Bruendel, Steffen: “Vor-Bilder des Durchhaltens. Die deutsche Kriegsanleihe-Werbung 1917/18”. In: Bauerkämper, Arnd / Julien, Elise (Eds.): Durchhalten! Krieg und Gesellschaft im Vergleich. Göttingen 2010: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 81-108, and Hoffmann, Detlef: “Der Mann mit dem Stahlhelm vor Verdun. Fritz Erlers Plakat zur sechsten Kriegsanleihe 1917”. In: Hinz, Berthold / Mittig, Hans-Ernst / Schäche, Wolfgang / Schönberger, Angela (Eds.): Die Dekoration der Gewalt. Kunst und Medien im Faschismus. Gießen 1979: Anabas, 101-114. Regarding the transformation of the soldierly/masculine image, cf. Hüppauf, Bernd: “Schlachtenmythen und die Konstruktion des ‘Neuen Menschen’”. In: Hirschfeld, Gerhard / Krumeich, Gerd (Eds.): Keiner fühlt sich hier mehr als Mensch… Erlebnis und Wirkung des Ersten Weltkrieges. Essen 1993: Klartext, 43-84; Ulrich, Bernd: “Krieg der Nerven, Krieg des Willens”. In: Werber, Niels / Kaufmann, Stefan / Koch, Lars (Eds.): Erster Weltkrieg. Kulturwissenschaftliches Handbuch. Stuttgart/Weimar 2014: Metzler, 232-258; and Reulecke, Jürgen: “Vom Kämpfer zum Krieger – Zum Wandel der Ästhetik des Männerbildes während des Ersten Weltkriegs”. In: Autsch, Sabiene (Ed.): Der Krieg als Reise. Der Erste Weltkrieg – Inneneinsichten. Siegen 1999: Carl Böschen, 52-62.

In addition, theatre as a “cultural practice of great contemporary relevance and as an important public forum” also participated in the public discourse about heroic endurance.13Baumeister, Martin: Kriegstheater. Großstadt, Front und Massenkultur 1914–1918. Essen 2005: Klartext, 7. Translation by Daniel Hefflebower. Particularly in Germany, the subject of numerous stage plays was the change in warfare and the persistence of the war that it entailed. These plays invoked the patriotism, honour, loyalty, camaraderie, steadfastness and endurance of the military. Representative for such plays was Paul Seiffert’s (1866–1939) war drama with the telling title Dennoch durch! (“Through nevertheless!” – 1917). The three-parter dramatises the war volunteers reporting for duty in September 1914 and their departure for the Western front (I), the soldiers waiting for the command to attack in a dugout near Soissons in January 1915 (II) and the arrival of the news of the protagonist Georg’s hero’s death at his family home (III). Act II, which constitutes essentially an examination of trench warfare and its implications, is enlightening with regard to the subject of enduring. The soldiers’ limited scope of action, which is also semanticised in the dramatic space, is significant. The dugout is cramped and dark; evokes the feeling of being trapped and is equated to a mole’s burrow.14Cf. Seiffert, Paul: Dennoch durch! Deutsches Schauspiel aus dem Weltkriege. Berlin 1917: Rohde, 26. While the fighting has already begun in the distance, the order is still to wait and maintain their position. The soldiers’ options are therefore limited to either ‘holding out until the command to attack’ or succumbing to the pugnacity manifesting itself as a physical desire and attacking early. The latter, however, would lead to certain defeat. Only patiently waiting and enduring, according to the text, guarantees victory in this battle and, in metonymical correlation, victory in the entire war. Hence the second act consists less of concrete action than it does the soldiers’ discussions on the command to wait. The soldiers are divided into two camps. On the one side, there is Georg, who has been assigned squad leader and is obediently following the order to wait, even if he is bemoaning the superhuman strain to not act.15Cf. e.g. Seiffert: Dennoch durch!, 1917, 25, 30. The rest of the squad, on the other hand, who again and again press to take the offensive and whom Georg tries to keep from doing that16Cf. in particular Seiffert: Dennoch durch!, 1917, 26-31., serves as foils. Georg’s wrangling is thereby projected onto the squad; the internalised agonality is externalised and made visible for the audience. Georg manages finally to convince his squad of the need to wait and endure, despite the difficulties in the trench, like the cold and wet conditions, but also the tediousness and boredom. In the meantime, the order is not made problematic at all, and in the text of the play, it is considered certain that following the order will guarantee the safety of the homeland. Georg’s actions are determined solely by an ethos of duty towards his fatherland:

“Warum des Schützengrabens Maulwurfsöde? […]

Warum nur können wir in soviel Dreck und Graus –

warum nur wollen wir im Höllengraben

ganz stille – feste – zähe – übermenschlich warten?!?

Weils nötig ist fürs Vaterland!

[…]

Und wer des Schützengrabens schwere Wartezeit

durch ungeduldges Stürmen stört –:

wer gar in feiger Seelenmattigkeit

nur eine einzge Lücke beut dem Feinde –:

der bringt das ganze Vaterland in Not.

Drum für die liebe Heimat,

für unsre Väter, Mütter und Geschwister

ist uns der Schützengraben not. –

Ists schwer auch – dennoch durch!”

The soldiers then join together in chorus with “Wir wollen warten!” (“We want to wait!”).17Seiffert: Dennoch durch!, 1917, 31. In Georg’s address and the reaction of his squad, it becomes clear that the waiting situation is one brought about by outside factors, but one that informs a positioning of the soldiers. After Georg convinces the squad of the necessity to wait and endure, the soldiers actively and knowingly adopt an expectant attitude, redefining their waiting as a self-determined action. In a kind of oath, the squad vows: “wir halten zähe durch, bis wirs erreicht: den Sieg!” (“we will endure tenaciously until we have achieved it: victory!”).18Seiffert: Dennoch durch!, 1917, 38.

5.2. Cycling

The novel Le Tour de Souffrance by André Reuze from 192519Reuze, André: Le Tour de Souffrance. Paris 1925: Fayard. The German translation: Reuze, André: Giganten der Landstraße: ein Rennfahrer-Roman. Transl. by Fred Antoine Angermayer. Berlin 1928: Büchergilde [and also: Reuze, André: Giganten der Landstraße: ein Tour-de-France-Roman. Transl. by Fred Antoine Angermayer. Berlin 1998: SVB Sportverlag] deviates in some places considerably from the original. The translations are taken hereinafter from the 1998 edition. can be described as an endurance narrative. Dedicated to “Héros inutiles. Héros quand même” (“Useless heroes. Heroes nonetheless”), the text dramatises the Tour de France, as its title suggests, like an obstacle course that tests the limits of the cyclists’ physical and mental resilience.20For further discussion of the following, cf. also Gamper, Michael: “Körperhelden. Der Sportler als ‘großer Mann’ in der Weimarer Republik”. In: Fleig, Anne / Nübel, Birgit (Eds.): Figurationen der Moderne. Mode, Sport und Pornographie. München 2001: Wilhelm Fink, 145-166; and the chapter titled “The Géants de la Route: Gender and Heroism”. In: Thompson, Christopher: The Tour de France. A Cultural History. Berkeley et al. 2008: University of California Press, 95-140. To endure until the end of the Tour is the athletic challenge and precondition for victory. The sports journalist Ravenelle writes: “Oui, monsieur, c’est ça le Tour. Il ne s’agit seulement de pédaler avec ses muscles, avec sa volonté et puis à coup de drogues […], il faut rester sur la selle malgré les courbatures, les furoncles, les plaies, pendant un mois et 5.416 kilomètres.”21Reuze: Tour, 1925, 17. Duration and finality, the principles of enduring, structure the text: the novel begins on the eve of the Tour; tells of the competition in the order of its daily stages; and closes with the entry into Parc des Princes stadium and the victory of the young cyclist Chevillard. With Ravenelle and the painter Manguy as their proxies, who accompany the Tour by car, readers follow the erratic action, which gradually forces figures temporarily leading the action to quit. The narrator soberly registers this constant shrinkage of the field; those cyclists who continue to endure become “survivants” (“survivors”). The adverse conditions of the race like the weather and the road, falls and flat tyres show in the maltreated bodies of the Tour participants such that the struggle against the mountains, heat and defective material appears as a struggle against oneself. The conditions of the act of endurance and the traces that they leave on the bodies of the athlete are correlated with one another in this way. This can be seen conspicuously in the frequently used phrase “X a crevé”, which metonymically transfers the bursting of a bicycle tyre tube onto the cyclist himself.

In their enduring, however, the cyclists are simultaneously “magnifique et pitoyable” – just as magnificent as they are pitiful. Alternating between these poles of admiration and commiseration, Reuze’s novel portrays endurance heroes whose heroic status is in danger of being upended. To be sure, there are certainly passages that justify the dedication to the heroes of the Tour. For instance, when the former Tour winner Tampier is making the mountain climb on Col d’Aubisque: “On eût dit que, centaure moderne s’élevant vers l’infini au-dessus des forces humaines, il allait par delà les cimes, retourner à la légende.”22Reuze: Tour, 1925, 148 f. These heroizing attributions, however, are contrasted by deconstructions of the hero that also draw their effectiveness from the portrayal of the act of endurance. Besides the previously mentioned emphasis of the physical suffering with which the cyclists are made into pitiful instead of admirable figures, the cynicism of the Tour organisers for instance bears pointing out in this regard. The novel reflects on that cynicism, and even discusses it as part of the plot. It is recurringly pointed out that the cyclists’ enduring and rising-above-themselves, indeed their heroization, ultimately serve economic ends. “Tant d’énergie galvanise la foule. Pour entretenir chez celle-ci un enthousiasme nécessaire on a d’année en année, rendu l’itinéraire plus pénible et donné des tours de vis au garrot du règlement. Avec ça on fait, sinon des dieux, du moins des idoles”23Reuze: Tour, 1925, 24. For more on the link between the sport hero and celebrity, cf. also Inglis, Fred: A Short History of Celebrity. Princeton u. a. 2010: Princeton University Press., says Ravenelle, thereby encapsulating the link between heroization and effective advertising. Extorted and cheated by the management, obliged by contract to overburden themselves athletically, by which they place their health on the line, and – metaphorically – chased by the train of support vehicles24For instance: “Les autos aux énormes yeux de feu étaient devenues de rugissants monstres de légende, lancés sur la fuite terrifiée d’êtres falots et frénétiques.” (Reuze: Tour, 1925, 27)., the cyclists appear stripped of their agency.

Reuze’s novel is therefore characterised by a manner of portraying endurance that not only creates heroes, but also questions them. In their oppositeness, the French title of the novel, on the one hand, and its translation into German, on the other hand, secure this ambivalence: while the title of the original foregrounds the suffering and physical strain of athletic endurance with the help of an untranslatable wordplay, the translation Giganten der Landstraße (Giants of the Road), which was published only three years later, asserts a heroization of enduring, which the novel as such ultimately does not achieve.

6. Einzelnachweise

- 1Detering, Nicolas: “Heroischer Fatalismus. Denkfiguren des ‘Durchhaltens’ von Nietzsche bis Seghers.” In: Literaturwissenschaftliches Jahrbuch, Neue Folge 60 (2019), 317-339. Key ideas of this article, especially with regards to the definition of ‘durchhalten’ (to endure), are due to Detering’s work as well as a workshop on this topic organised by the Sonderforschungsbereich 948/Project D6 on 19 January 2018.

- 2Bluhm, Lothar: Auf verlorenem Posten. Ein Streifzug durch die Geschichte eines Sprachbildes. Trier 2012: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier.

- 3Cf. Weber, Max: Economy and Society. A New Translation. Ed. and transl. by Keith Tribe. Cambridge, Massachusetts 2019: Harvard University Press, 103. (For the original German text cf. Weber, Max: Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Grundriss der verstehenden Soziologie. Studienausgabe hg. von Johannes Winckelmann. Erster Halbband. Köln/Berlin 1964: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 16.) For a more extensive look at Weber’s concept of ‘action’ and its usefulness for a heuristic of the heroic, cf. Aurnhammer, Achim / Klessinger, Hanna: “Was macht Schillers Wilhelm Tell zum Helden? Eine deskriptive Heuristik heroischen Handelns.” In: Jahrbuch der deutschen Schillergesellschaft 62 (2018), 127-149, 130-132.

- 4Detering: “Heroischer Fatalismus”, 2019, 321, lists the resilience of an antagonistic opponent, adverse weather conditions and time that simply never wants to end. That list bears amending with physical overexertion – in particular with regard to sport as a central domain of ‘enduring’ – but also with pressure at a social or political level, like Mandela’s example shows.

- 5The parallels primarily to stoicism are also drawn by Detering: “Heroischer Fatalismus”, 2019, 321.

- 6Finality as a central component of ‘enduring’ is also discussed by Detering: “Heroischer Fatalismus”, 2019, 320-321, but without establishing a connection to the attribution of meaning and legitimisation.

- 7Cf. Bluhm: Auf verlorenem Posten, 2012, 111-113, and Detering: “Heroischer Fatalismus”, 2019, 324.

- 8Regarding the popularity of this attitude in the Weimar Republic and the Nazi period, cf. Bluhm: Auf verlorenem Posten, 2012, 113-136; specifically regarding Thomas Mann, cf. Detering: “Heroischer Fatalismus”, 2019, 324-326.

- 9Weber: Economy and Society, 2019, 103. This type of action must be differentiated from the ‘purposive-rational’, ‘affectual/emotional’ and ‘traditional’ types of action (cf. ibid.).

- 10These typological characteristics are the result of discussions held at the Sonderforschungsbereich 948. They help in describing numerous different hero figures and their narratives. In the specific case, each of the characteristics can, but does not have to, mark the heroization or medialisation. Cf. also Tobias Schlechtriemen’s article on the ⟶Constitutive Processes of Heroic Figures.

- 11Cf. Reimann, Aribert: Der große Krieg der Sprachen. Untersuchungen zur historischen Semantik in Deutschland und England zur Zeit des Ersten Weltkriegs. Essen 2000: Klartext, 28-48.

- 12Regarding Fritz Erler’s poster, cf. Bruendel, Steffen: “Vor-Bilder des Durchhaltens. Die deutsche Kriegsanleihe-Werbung 1917/18”. In: Bauerkämper, Arnd / Julien, Elise (Eds.): Durchhalten! Krieg und Gesellschaft im Vergleich. Göttingen 2010: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 81-108, and Hoffmann, Detlef: “Der Mann mit dem Stahlhelm vor Verdun. Fritz Erlers Plakat zur sechsten Kriegsanleihe 1917”. In: Hinz, Berthold / Mittig, Hans-Ernst / Schäche, Wolfgang / Schönberger, Angela (Eds.): Die Dekoration der Gewalt. Kunst und Medien im Faschismus. Gießen 1979: Anabas, 101-114. Regarding the transformation of the soldierly/masculine image, cf. Hüppauf, Bernd: “Schlachtenmythen und die Konstruktion des ‘Neuen Menschen’”. In: Hirschfeld, Gerhard / Krumeich, Gerd (Eds.): Keiner fühlt sich hier mehr als Mensch… Erlebnis und Wirkung des Ersten Weltkrieges. Essen 1993: Klartext, 43-84; Ulrich, Bernd: “Krieg der Nerven, Krieg des Willens”. In: Werber, Niels / Kaufmann, Stefan / Koch, Lars (Eds.): Erster Weltkrieg. Kulturwissenschaftliches Handbuch. Stuttgart/Weimar 2014: Metzler, 232-258; and Reulecke, Jürgen: “Vom Kämpfer zum Krieger – Zum Wandel der Ästhetik des Männerbildes während des Ersten Weltkriegs”. In: Autsch, Sabiene (Ed.): Der Krieg als Reise. Der Erste Weltkrieg – Inneneinsichten. Siegen 1999: Carl Böschen, 52-62.

- 13Baumeister, Martin: Kriegstheater. Großstadt, Front und Massenkultur 1914–1918. Essen 2005: Klartext, 7. Translation by Daniel Hefflebower.

- 14Cf. Seiffert, Paul: Dennoch durch! Deutsches Schauspiel aus dem Weltkriege. Berlin 1917: Rohde, 26.

- 15Cf. e.g. Seiffert: Dennoch durch!, 1917, 25, 30.

- 16Cf. in particular Seiffert: Dennoch durch!, 1917, 26-31.

- 17Seiffert: Dennoch durch!, 1917, 31.

- 18Seiffert: Dennoch durch!, 1917, 38.

- 19Reuze, André: Le Tour de Souffrance. Paris 1925: Fayard. The German translation: Reuze, André: Giganten der Landstraße: ein Rennfahrer-Roman. Transl. by Fred Antoine Angermayer. Berlin 1928: Büchergilde [and also: Reuze, André: Giganten der Landstraße: ein Tour-de-France-Roman. Transl. by Fred Antoine Angermayer. Berlin 1998: SVB Sportverlag] deviates in some places considerably from the original. The translations are taken hereinafter from the 1998 edition.

- 20For further discussion of the following, cf. also Gamper, Michael: “Körperhelden. Der Sportler als ‘großer Mann’ in der Weimarer Republik”. In: Fleig, Anne / Nübel, Birgit (Eds.): Figurationen der Moderne. Mode, Sport und Pornographie. München 2001: Wilhelm Fink, 145-166; and the chapter titled “The Géants de la Route: Gender and Heroism”. In: Thompson, Christopher: The Tour de France. A Cultural History. Berkeley et al. 2008: University of California Press, 95-140.

- 21Reuze: Tour, 1925, 17.

- 22Reuze: Tour, 1925, 148 f.

- 23Reuze: Tour, 1925, 24. For more on the link between the sport hero and celebrity, cf. also Inglis, Fred: A Short History of Celebrity. Princeton u. a. 2010: Princeton University Press.

- 24For instance: “Les autos aux énormes yeux de feu étaient devenues de rugissants monstres de légende, lancés sur la fuite terrifiée d’êtres falots et frénétiques.” (Reuze: Tour, 1925, 27).

7. Selected literature

- Aurnhammer, Achim / Klessinger, Hanna: “Was macht Schillers Wilhelm Tell zum Helden? Eine deskriptive Heuristik heroischen Handelns”. In: Jahrbuch der deutschen Schillergesellschaft 62 (2018), 127-149.

- Baumeister, Martin: Kriegstheater. Großstadt, Front und Massenkultur 1914–1918. Essen 2005: Klartext.

- Bluhm, Lothar: Auf verlorenem Posten. Ein Streifzug durch die Geschichte eines Sprachbildes. Trier 2012: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier.

- Bruendel, Steffen: “Vor-Bilder des Durchhaltens. Die deutsche Kriegsanleihe-Werbung 1917/18”. In: Bauerkämpfer, Arnd / Julien, Elise (Eds.): Durchhalten! Krieg und Gesellschaft im Vergleich. Göttingen 2010: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 81-108.

- Detering, Nicolas: “Heroischer Fatalismus. Denkfiguren des ‘Durchhaltens’ von Nietzsche bis Seghers”. In: Literaturwissenschaftliches Jahrbuch, Neue Folge 60 (2019), 317-339.

- Gamper, Michael: “Körperhelden. Der Sportler als ‘großer Mann’ in der Weimarer Republik”. In: Fleig, Anne / Nübel, Birgit (Eds.): Figurationen der Moderne. Mode, Sport und Pornographie. München 2001: Wilhelm Fink, 145-166.

- Hoffmann, Detlef: “Der Mann mit dem Stahlhelm vor Verdun. Fritz Erlers Plakat zur sechsten Kriegsanleihe 1917”. In: Hinz, Berthold / Mittig, Hans-Ernst / Schäche, Wolfgang / Schönberger, Angela (Eds.): Die Dekoration der Gewalt. Kunst und Medien im Faschismus. Gießen 1979: Anabas, 101-114.

- Hüppauf, Bernd: “Schlachtenmythen und die Konstruktion des ‘Neuen Menschen’”. In: Hirschfeld, Gerhard / Krumeich, Gerd (Eds.): Keiner fühlt sich hier mehr als Mensch… Erlebnis und Wirkung des Ersten Weltkrieges. Essen 1993: Klartext, 43-84.

- Inglis, Fred: A Short History of Celebrity. Princeton et al. 2010: Princeton University Press.

- Reimann, Aribert: Der große Krieg der Sprachen. Untersuchungen zur historischen Semantik in Deutschland und England zur Zeit des Ersten Weltkriegs. Essen 2000: Klartext.

- Reulecke, Jürgen: “Vom Kämpfer zum Krieger – Zum Wandel der Ästhetik des Männerbildes während des Ersten Weltkriegs”. In: Autsch, Sabiene (Ed.): Der Krieg als Reise. Der Erste Weltkrieg – Inneneinsichten. Siegen 1999: Carl Böschen, 52-62.

- Reuze, André: Le Tour de Souffrance. Paris 1925: Fayard.

- Seiffert, Paul: Dennoch durch! Deutsches Schauspiel aus dem Weltkriege. Berlin 1917: Rohde.

- Thompson, Christopher: The Tour de France. A Cultural History. Berkeley u.a. 2008: University of California Press, 95-140.

- Ulrich, Bernd: “Krieg der Nerven, Krieg des Willens”. In: Werber, Niels / Kaufmann, Stefan / Koch, Lars (Eds.): Erster Weltkrieg. Kulturwissenschaftliches Handbuch. Stuttgart/Weimar 2014: Metzler, 232-258.

- Weber, Max: Economy and Society. A New Translation. Ed. and transl. by Keith Tribe. Cambridge, Massachusetts 2019: Harvard University Press .

8. List of images

- 1Fritz Erler: „Mann mit dem Stahlhelm vor Verdun“, 1917, Farblithographie, 72 x 55 cm, Druck von Fritz Maison München, The Imperial War Museum Posters Collection, Q 75995.Quelle: User:1970gemini / Wikimedia Commons (Zugriff am 26.10.2022)Lizenz: Gemeinfrei