- Version 1.0

- publiziert am 19. August 2022

Inhalt

1. Introduction

Heroic figures perform their deeds on their own. It is they who decide, who act, and who risk their lives. Hegel wrote that heroes in the ‘heroic age’ were still fully responsible for their deeds.1Cf. Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: Aesthetics. Lectures on Fine Art. Vol. I. Transl. by T. M. Knox. Oxford 1975 [Repr. 2010]: Clarendon Press, 179-195. (Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: Vorlesungen über die Ästhetik I. Frankfurt a. M. 1997: Suhrkamp, 236-255.) Therefore, for Hegel, there could no longer be heroes in a modern, civil society which is characterised by the division of labour: Numerous members are involved in the course of each event, responsibility is spread, and it is “no longer a matter of individual heroism and the virtue of a single person”.2Hegel: Aesthetics I, 1975 [2010], 183. (Hegel: Vorlesungen über die Ästhetik I, 1997, 241.) Historically, Hegel’s prognosis has not come true. Even in the so-called ‘post-heroic age’, heroic figures are all around us.3For a critical analysis of the discourse of post-heroism cf. Bröckling, Ulrich: Postheroische Helden. Ein Zeitbild. Berlin 2020: Suhrkamp. However, it remains true for the portrayal of heroes that they are usually shown as lone fighters with sole responsibility. Heroic stories concentrate on one protagonist and they place a strong and active individual figure at their centre.4In many contexts ‘the hero’ and ‘the protagonist’ are used synonymously. Drive and determination are both essential hallmarks of the hero. It is therefore not surprising that, along with ‘heroic death’ and ‘heroic bravery’, ‘heroic deed’ is one of the few established idioms which comprise ‘hero-’.5On the relationship between heroic action and heroic deed cf. Aurnhammer, Achim / Klessinger, Hanna: “Was macht Wilhelm Tell zum Helden? Eine deskriptive Heuristik heroischen Handelns”. In: Jahrbuch der deutschen Schillergesellschaft 62 (2018), 127-149.

As with the other central features of ⟶heroic figures (extraordinariness, ⟶transgressiveness, affective and moral charge, and agonality), this analysis aims to show how the traits of heroic agency emerge. Heroic agency is analysed as the result of a ⟶constitutive process.6Cf. in addition, by way of introduction Schlechtriemen, Tobias: “Constitutive Processes of Heroic Figures”. In: Compendium heroicum. Ed. by Ronald G. Asch, Achim Aurnhammer, Georg Feitscher, Anna Schreurs-Morét, and Ralf von den Hoff, published by Sonderforschungsbereich 948 “Heroes – Heroizations – Heroisms” at the University of Freiburg, Freiburg 2022-08-19. DOI: 10.6094/heroicum/kphfe1.0.20220819. This heuristic was developed on the basis of the analysis of a European source corpus and is bound by its orientation to this context. For other cultural contexts, the analytical tools must be adapted or modified accordingly. Within this process agency is attributed to and concentrated on the respective figure.7Cf. on the concentration of human agency: Schechtriemen, Tobias: “The Hero as an Effect: Boundary Work in Processes of Heroization”. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 17-26. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/03 (for the original publication in German see Schechtriemen, Tobias: “Der ‘Held’ als Effekt. Boundary work in Heroisierungsprozessen”. In: Berliner Debatte Initial 29.1 (2018), 106-119); Gölz, Olmo: “Heroes and the many: Typological reflections on the collective appeal of the heroic. Revolutionary Iran and its implications.” In: Thesis Eleven (2021), 1-19. DOI: 10.1177/07255136211033168 examines, in a kind of reversed analytical perspective, not how the isolation of the heroic figure comes about, but what collective and collectivising effect such figures of deviation, which call for imitation, produce. In order to trace it, we start with a concrete heroic figure and reconstruct how this trait came about. For this purpose, actor-network theory is applicable and will be introduced as an analytical tool below.

Actor-network theory – expanded to include approaches from literature and media studies – is used to examine attribution, communication and representation processes through which a person is first made into a hero. Accordingly, the heroic figure represents a ‘real fiction’8Cf. Bröckling, Ulrich: Das unternehmerische Selbst. Soziologie einer Subjektivierungsform. Frankfurt a. M. 2007: Suhrkamp, 35-38. which is generated via communication and media, irrespective of whether a real historical person is the starting point or not. If a historical person forms the starting point, the concentration of agency takes place as a historical process, as a history of transmission. However, in the case of fictional representations it can also be examined how the strong agency emerges as a communication and representation effect.

2. On the constitution of heroic agency

Heroic agency can be characterised by the fact that a) it refers to human action, b) it involves only one person and the many tend to be passive in comparison, and c) the manner of action can be characterised by activity, power and strength. According to Weber, this human action is also framed as “meaningful”9Weber, Max: Economy and Society. A New Translation. Ed. and transl. by Keith Tribe. Cambridge (Massachusetts) / London 2019: Harvard University Press. (Weber, Max: Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Bd 1. Tübingen 1956: J.C.B Mohr, 3.), because it is based on a motivation and a decision. Consequently, it represents a conscious action – such as consciously accepting personal risk, breaking laws, etc. – for which the acting person can be held responsible by others.

The sociological concept of ‘agency’ may be useful in examining the more specific phenomenon of ‘heroic agency’. It can help analyse “who or what possesses or is attributed what capacity to act.”10Helfferich, Cornelia: “Einleitung: Von roten Heringen, Gräben und Brücken. Versuche einer Kartierung von Agency-Konzepten”. In: Helfferich, Cornelia / Bethmann, Stephanie / Hoffmann, Heiko / Niermann, Debora (Eds.): Agency. Die Analyse von Handlungsfähigkeit und Handlungsmacht in qualitativer Sozialforschung und Gesellschaftstheorie. Weinheim / Basel 2012: Beltz Juventa, 9-39, 10. In this formulation it already becomes clear that not only individual persons exhibit or are attributed agency, but also other social actors such as institutions or non-human actors.11Cf. Emirbayer, Mustafa / Mische, Ann: “What Is Agency?” In: American Journal of Sociology 103.4 (1998), 962-1023. The actor-network theory, as developed by Bruno Latour, offers a fruitful heuristic for this.12Cf. for example Latour, Bruno: We Have Never Been Modern. Transl. by Catherine Porter. Cambridge (Massachusetts) 1993: Harvard University Press; Latour, Bruno: Reassembling the Social. An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford a.o. 2007: Oxford University Press; Belliger, Andréa / Krieger, David J. (Eds.): ANThology. Ein einführendes Handbuch zur Akteur-Netzwerk-Theorie. Bielefeld 2006: Transcript.

What does Latour understand by an ‘actor’?13Cf. Schüttpelz, Erhard: Elemente einer Akteur-Medien-Theorie. In: Schüttpelz, Erhard / Thielmann, Tristan (Eds.): Akteur-Medien-Theorie. Bielefeld 2013: Transcript, 9-67. This brief presentation of the ANT approach is based on the corresponding section in Schlechtriemen, Tobias: “The Hero and a Thousand Actors. On the Constitution of Heroic Agency”. In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen 4.1 (2016), 17-32. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2016/01/03 . From semiotics he adopts the concept of the ‘actant’. According to this, not only the main character acts in a text; rather, all the instances mentioned in the text contribute their part of a story. These include the various characters, but also non-human actors, individual as well as collective, figurative as well as non-figurative.14Cf. Latour, Bruno: The Pasteurization of France. London 1988: Harvard University Press, 252, FN 11 and Latour: Reassembling the Social, 2007, 53 ff., referencing Greimas, Algirdas Julien / Courtès, Joseph: Sémiotique. Dictionnaire raisonné de la théorie du langage. Paris 1979: Hachette Université. Regarding the notion of “actor” cf. also Latour: Reassembling the Social, 2007, 43-86. Latour transfers this concept of ‘actors’ or ‘actants’ to the experimental situation in a natural science laboratory. In an experiment, there is analogously a certain arrangement of chemical substances, technical apparatuses, human intentions, and so on. All actors are involved in the outcome of the experiment – it may fail because of a technical device, the chemical substance may react unexpectedly, a scientist may overlook something, etc. All actors involved in such a situation interact with each other and in this way form an ‘actor-network’.

An actor-network is arranged as a ‘structure of interdependence’. The elements involved do not enter this network as, so to speak, finished and fixed actors. Rather, they become what they represent only through interactions with the other actors. Consequently, there are no unchanging elements that make up the network. However, the unity of a network does not determine its elements ‘top down’ either. Instead, there is mid-level interaction at which the individual actors have a say in what happens, but also which effects are achieved by the overall structure.15Cf. for this purpose the concept of ‘Assemblage’, as developed by DeLanda following Deleuze. DeLanda, Manuel: A New Philosophy of Society. Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. London / New York: Continuum 2006.

After this approach proved successful for describing the complex processes in the laboratory, Latour proposed it as an alternative for sociological descriptions in principle. In his view, these were limited to social actors and ignored the role of all other participants. However, to Latour it seemed important to describe the socio-technical networks as a whole and not to make a categorical separation in advance that excludes all natural things, technical objects, etc.16The elements of a network can appear in three roles: as intermediaries, who do not change what they transport; as mediators, who translate, transform what they pass on; and as actors, i.e. those mediators who obtain clear outlines through figuration. The principle of symmetry applies here first and foremost: everyone and everything should first be included in the same way regarding their participation in the overall event.

Moreover, actors can form a chain of transmission through which information or even scientific references travel, which will be instructive for the analysis of media below. The interlinked actors act as ‘intermediaries’. Here, Latour adopts the concept of ‘traduction’ from Michel Serres.17His colleague Michel Callon refers to Serres, Michel: Hermes 3. La traduction. Paris 1974: Éd. de Minuit. Mediators not only transport a piece of information in a chain of transmission, but they transform it. Actors as intermediaries are thus not merely means of transport, but they translate, they transform, that which they transmit.

Against this analytical background, it becomes clear that human agency is a specific form of agency whose constituent elements must be considered. In the case of the heroic figure, agency is given a face, a name, a gender, is linked to a biographical narrative, etc. The following analysis also draws on methods from literature and media studies, which are oriented towards the respective media of representation and their own logics. In addition, there is an overlap in content with the process of personalisation, which will be specifically dealt with elsewhere.

3. A case study: Louis Pasteur and the historical reconstruction of the concentration of agency

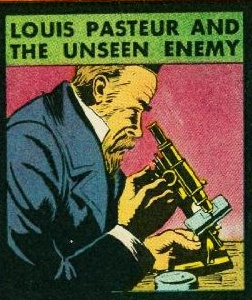

The concentration of agency is examined below using the example of a science hero, Louis Pasteur.18This example lends itself because Latour develops his approach on Pasteur and lactic acid yeast, among others. Cf. Latour: The Pasteurization of France, 1988 and chapter 4: “From Fabrication to Reality. Pasteur and His Lactic Acid Ferment”. In: Latour, Bruno: Pandora’s Hope. Essays on the Reality of Science Studies, Cambridge (Massachusetts) / London 1999: Harvard University Press, 113-144. As a result of the process to be analysed, Louis Pasteur appears as an outstanding scientist who saved millions of lives with his discoveries of microbes and vaccines. The website ‘Science Heroes’ lists such heroes and actually counts how many lives they saved.19Online at: https://scienceheroes.com (accessed on 14.10.2019). In Pasteur’s case, it is acknowledged that the number cannot be precisely determined. However, because his research was so fundamental to many other scientific achievements, he is counted among the “Science Heroes Legends”.20Online at: https://scienceheroes.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=184&Itemid=183 (accessed on 14.10.2019). In France, streets named after Pasteur can be found in almost every city, there are countless Pasteur monuments (see fig. 1), and he appears in comics (see figs. 3 and 4) and as a role model in school textbooks. In the television show “Le plus grand Français de tous les temps” (broadcast in 2005 on France 2), when asked who the most important French person of all time was, Pasteur was voted second behind Charles de Gaulle.21Wirtén, Eva Hemmungs: The Pasteurization of Marie Curie. A (meta)biographical experiment. In: Social Studies of Science 45.4 (2015), 597-610 also refers to this survey. However, Pasteur is not only a formative figure in France, but is also among the revered role models of science in many countries.22‘Pasteurise’ is a common verb in very many languages and a constantly practised procedure, just as vaccination and basic hygiene measures shape our daily lives.

How did this transnational adoration of Louis Pasteur as a hero of science come about? Since we are dealing with a historical person as well as historical events, it is possible to reconstruct how the heroic agency formed over time. Pasteur’s most important heroic deed and the starting point of his ⟶heroization was his experiment at Pouilly-le-Fort.23Regarding these events, cf. Vallery-Radot, René: Louis Pasteur. Sein Leben und Werk. Freudenstadt 1948 [1900]: Schwarzwald Verlag, 441-455 and Geison, Gerald L.: The Private Science of Louis Pasteur. Princeton 1995: Princeton University Press, Kap. 6: “The Secret of Pouilly-le-Fort: Competition and Deception in the Race for the Anthrax Vaccine”, 145-176. In 1881, Pasteur decided to publicly demonstrate the effects of his vaccinations on animals at a farm in a small suburb of Paris, Pouilly-le-Fort near Melun. He chose the following experimental set-up for this: out of 50 sheep, 25 were inoculated with his vaccine twice over the course of a month.24At the last moment, two sheep were replaced with two goats and additionally six out of ten cows were vaccinated. Cf. Geison: The Private Science of Louis Pasteur, 1995, 147, FN 7. All 50 sheep were subsequently infected with the anthrax virus. Three days later, Pasteur and his two collaborators Émile Roux and Charles Chamberland returned to Pouilly-le-Fort and, in the presence of a large audience and the press, checked which sheep were still alive. The result was clear: all the vaccinated animals had survived, while all the non-vaccinated ones had died, except for two that were seriously ill. It was considered a great triumph and news of it quickly spread around the world.

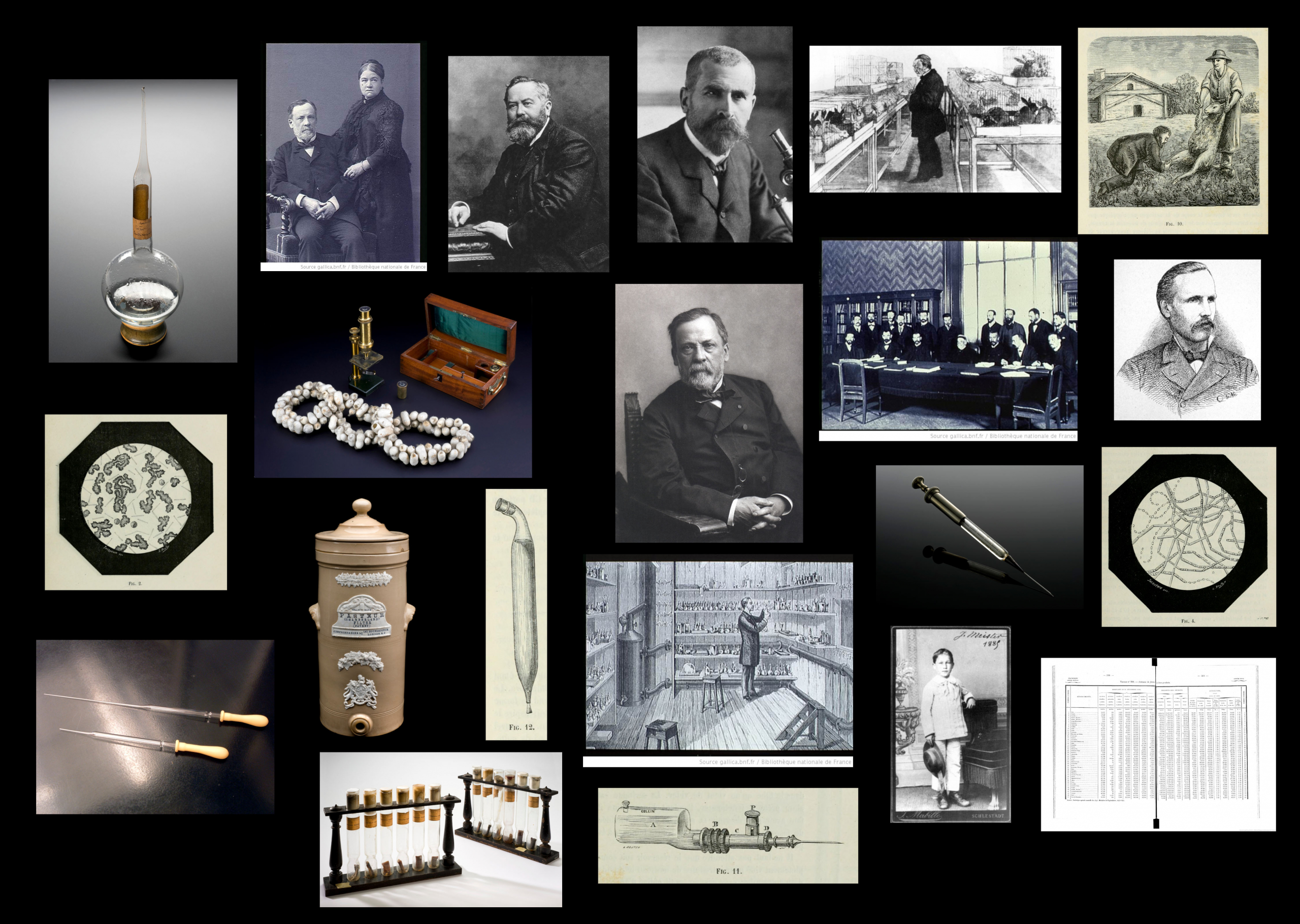

Many actors were involved in the experiment at Pouilly-le-Fort: Pasteur’s competitors in the academy, his scientific collaborators, as well as politicians, spectators, and so on. However – as can be demonstrated using the actor-network theory – not only human actors were involved, but also the technical equipment, the whole technical arrangement in the laboratory, the sheep, the microbes, and finally the media, which reported about it worldwide following the events on the farm. It was a network of many different actors who were directly involved in the situation and who all helped shape the events in their own way (see fig. 2).25How this actor-network is shaped by each individual element, but how the elements in turn also only receive properties conditioned by the network, can be illustrated by the example of the syringe. Cf. Schlechtriemen: “The Hero and a Thousand Actors”, 2016, 23-25. I would like to thank Georg Feitscher for his help in developing the illustration.

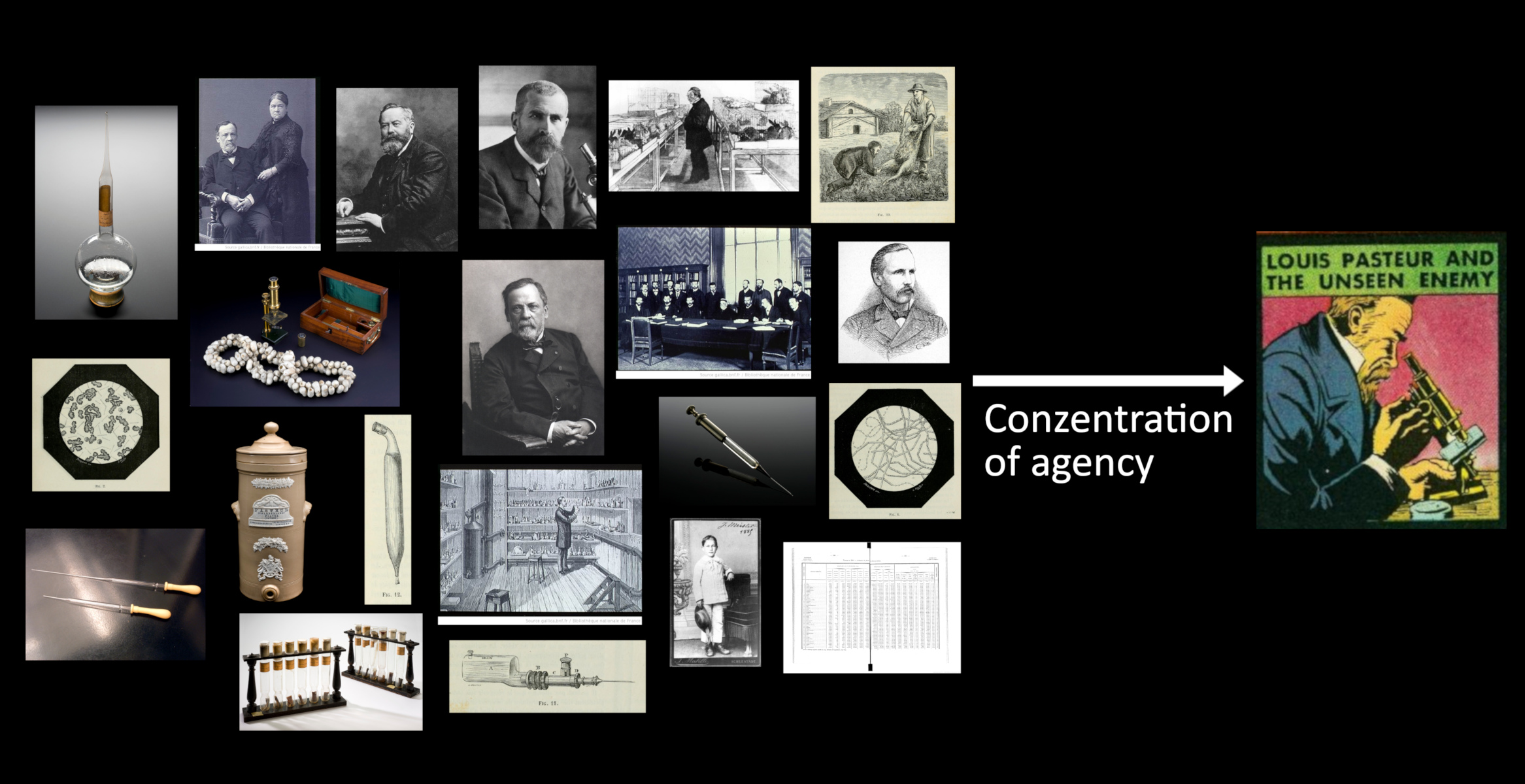

The advantage of the heuristic of the actor-network theory is that it initially includes all the different actors. Thereby, it enables the observation of the following process with its boundary drawings: In the transmission of the events of Pouilly-le-Fort, the agency initially distributed among many actors becomes increasingly concentrated on Pasteur as the central figure. While the first depictions still show many other actors, after some time only Pasteur remains with a few accompanying figures. Now the active hero is in the focus, the agency of almost all other participants is faded out – with the exception of those who belong ‘emblematically’, so to speak, to the heroic figure in question.26Part of this is that the focus is on the male science hero. In the film version of Pasteur’s life The Story of Louis Pasteur (from 1936, directed by William Dieterle), the rational scientist is juxtaposed with an irrational mystic, almost a witch figure. For example, Pasteur is often accompanied by his test tube or his microscope, as on the cover of Real Heroes magazine, where Pasteur is shown fighting his “unseen enemy” alongside war heroes (see figs. 3 and 4).

Part of the heroization process, then, consists in concentrating agency on one central figure, tending to attribute all activity to him. Through this process of concentration, the emergence of the property of strong agency can be described (see fig. 5).

Moreover, in the process that takes place between the actor-network on the left and the heroized figure on the right, a separation is made between people and things. If one still has a mixed constellation at first, what remains at the end is the acting human. Within the framework of the heuristic, it thus also becomes clear that it is an important part of heroization that the hero is depicted as a human being, with a face, a gender, and a name, that they appear as an agent, and that there exist biographical narratives. Thus, in parallel to the concentration of agency, a process takes place that could be called ‘anthropomorphisation’ or ‘personalisation’ (see fig. 6).27Anthropomorphisation here refers to the giving of a human form. In this respect, the concept is broader here than is usual in literary studies.

Furthermore, different media are involved in the concentration of agency on a central acting human being. An example of this is the monument depicting Pasteur in a sublime seated position (see fig. 1). Part of the media-specific representation is that monuments typically only show a handful or even only one person. In addition, this figure is ‘placed on the pedestal’ and often presented larger than life, so that the viewer must look up at it. The site of installation is also deliberately chosen and in its own way contributes to the concentration of the agency: Monuments are often positioned in prominent places in the cityscape. Sometimes these places are used for ceremonial gatherings, in the middle of or above which the person depicted as a monument is enthroned. By means of isolation, prominence through size, and appropriate placement in the cityscape, monuments contribute to the perception of the depicted hero as acting alone (quantitatively), as a powerful and significant figure (qualitatively).28The monument in Budapest commemorating the 1956 Hungarian National Uprising (erected in 2006 by the i-ypszilon group) symbolises the concentration effect of ordinary monuments in a very fitting way – and is itself aligned with the now empty site of the former Stalin monument. For the advice on this I thank Olmo Gölz. As mediators in Latour’s sense, they translate and transform what is depicted. Moreover, the monument presents Pasteur in a bodily and human form and thus contributes to anthropomorphisation.29It is precisely this aspect of physical presentation that poses a problem in Muslim contexts – as does visualisation in general – which calls for other forms of representation such as writing or, at best, portraiture.

What has been exemplarily shown here in relation to monuments applies to all media. They each exhibit specific possibilities and affordances by which they can participate in the dynamics of the concentration and fading out that take place in the course of transmission and give the heroic figure its strong agency as well as its human form. In this sense, the hero does not exist until he has been formed by media intermediaries; the various media each participate in his constitution in their own way, bringing into play already existing aesthetic forms of representation (⟶prefigurations), but also shaping new “pathos formulae” of the heroic. What remains (for the time being) is the one heroic figure with its strong agency and human face.

For the purpose of analysing heroization processes this means: Firstly, that the actors originally involved in the event or in a current situation but obscured by concentration elsewhere can be reconstructed.30Historical reconstructions have the additional difficulty that some of the actors involved did not survive or have not been preserved. For this purpose, the heuristics of the actor-network theory represent a helpful analytical tool. Secondly, that narratology, art and media analyses can show the ways in which different media participate in the processes of concentration of agency as well as anthropomorphisation.

If one assumes that an event does not necessarily have to be transmitted in such a way that a human being forms the center of action, one can ask about the function of this form of representation.31The Sensory Ethnography Lab at Harvard University is specifically looking for alternative ways of representation. Online at: http://sel.fas.harvard.edu/index.html (accessed on 14.11.2019). Pasteur is primarily presented as a hero of science. The complex historical situation of Pouilly-le-Fort is thematically focused in this way. On one hand, this reflects the conviction or desire for a far-reaching human ability to act, according to which an event can be controlled by a human being. On the other, it ‘gives a face’ to scientific practices and research processes. The sometimes abstract and complex research dynamics – microbes, moreover, are an all but invisible object of investigation – are simplified and illustrated by the human figure of the researcher and his heroic actions. Accordingly, scientific heroes exercise a formative function in the external representation of science, even if this has been repeatedly criticised as simplistic.32Cf. the contributions to the discussion by Athene, Donald: “How many scientists does it take to make a discovery?”. In: The Telegraph, 17 September 2012; Athene, Donald: “In science today, a genius never works alone”. In: The Observer, 3 February 2013. Following on from this, alternative forms of representation should be addressed. As far as the form of the narrative is concerned, for example, it is about the distribution of agency among many participants. For Latour, the quality of a report can be measured by how many actors have contributed to it. The more actors speak, Latour asserts, and are thus perceived as actively involved in a situation, the more likely it is that an account will do justice to the complexity of the events.33Cf. Latour: Reassembling the Social, 2007, 128 f. Brecht, too, has his ‚worker who reads‘ ask about those blanked out in heroic stories: “Who built the seven gates of Thebes? / […] Young Alexander conquered India. / Was he alone? / Caesar defeated the Gauls. / Did he not have so much as a cook with him?” and closes with “So many reports / So many questions.” Brecht, Bertolt: Questions of a worker who reads. In: The Collected Poems of Bertolt Brecht. Transl. and ed. By Tom Kuhn and David Constantine w. the assistance of Charlotte Ryland. New York / London 2019: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 675. (Originally: “Wer baute das siebentorige Theben? […] Der junge Alexander eroberte Indien. / Er allein? / Cäsar schlug die Gallier. / Hatte er nicht wenigstens einen Koch bei sich?” und closes with “So viele Berichte / So viele Fragen.” Brecht, Bertolt: Fragen eines lesenden Arbeiters. In: Werke. Große kommentierte Berliner und Frankfurter Ausgabe. Vol. 12: Gedichte 2. Berlin / Weimar / Frankfurt a. M. 1988, 29.) I would like to thank Achim Aurnhammer for pointing this out. Seen in this light, heroic stories appear to be oversimplifying narratives, at least if they claim to adequately depict a complex process.

4. Einzelnachweise

- 1Cf. Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: Aesthetics. Lectures on Fine Art. Vol. I. Transl. by T. M. Knox. Oxford 1975 [Repr. 2010]: Clarendon Press, 179-195. (Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: Vorlesungen über die Ästhetik I. Frankfurt a. M. 1997: Suhrkamp, 236-255.)

- 2

- 3For a critical analysis of the discourse of post-heroism cf. Bröckling, Ulrich: Postheroische Helden. Ein Zeitbild. Berlin 2020: Suhrkamp.

- 4In many contexts ‘the hero’ and ‘the protagonist’ are used synonymously.

- 5On the relationship between heroic action and heroic deed cf. Aurnhammer, Achim / Klessinger, Hanna: “Was macht Wilhelm Tell zum Helden? Eine deskriptive Heuristik heroischen Handelns”. In: Jahrbuch der deutschen Schillergesellschaft 62 (2018), 127-149.

- 6Cf. in addition, by way of introduction Schlechtriemen, Tobias: “Constitutive Processes of Heroic Figures”. In: Compendium heroicum. Ed. by Ronald G. Asch, Achim Aurnhammer, Georg Feitscher, Anna Schreurs-Morét, and Ralf von den Hoff, published by Sonderforschungsbereich 948 “Heroes – Heroizations – Heroisms” at the University of Freiburg, Freiburg 2022-08-19. DOI: 10.6094/heroicum/kphfe1.0.20220819. This heuristic was developed on the basis of the analysis of a European source corpus and is bound by its orientation to this context. For other cultural contexts, the analytical tools must be adapted or modified accordingly.

- 7Cf. on the concentration of human agency: Schechtriemen, Tobias: “The Hero as an Effect: Boundary Work in Processes of Heroization”. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 17-26. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/03 (for the original publication in German see Schechtriemen, Tobias: “Der ‘Held’ als Effekt. Boundary work in Heroisierungsprozessen”. In: Berliner Debatte Initial 29.1 (2018), 106-119); Gölz, Olmo: “Heroes and the many: Typological reflections on the collective appeal of the heroic. Revolutionary Iran and its implications.” In: Thesis Eleven (2021), 1-19. DOI: 10.1177/07255136211033168 examines, in a kind of reversed analytical perspective, not how the isolation of the heroic figure comes about, but what collective and collectivising effect such figures of deviation, which call for imitation, produce.

- 8Cf. Bröckling, Ulrich: Das unternehmerische Selbst. Soziologie einer Subjektivierungsform. Frankfurt a. M. 2007: Suhrkamp, 35-38.

- 9Weber, Max: Economy and Society. A New Translation. Ed. and transl. by Keith Tribe. Cambridge (Massachusetts) / London 2019: Harvard University Press. (Weber, Max: Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Bd 1. Tübingen 1956: J.C.B Mohr, 3.)

- 10Helfferich, Cornelia: “Einleitung: Von roten Heringen, Gräben und Brücken. Versuche einer Kartierung von Agency-Konzepten”. In: Helfferich, Cornelia / Bethmann, Stephanie / Hoffmann, Heiko / Niermann, Debora (Eds.): Agency. Die Analyse von Handlungsfähigkeit und Handlungsmacht in qualitativer Sozialforschung und Gesellschaftstheorie. Weinheim / Basel 2012: Beltz Juventa, 9-39, 10.

- 11Cf. Emirbayer, Mustafa / Mische, Ann: “What Is Agency?” In: American Journal of Sociology 103.4 (1998), 962-1023.

- 12Cf. for example Latour, Bruno: We Have Never Been Modern. Transl. by Catherine Porter. Cambridge (Massachusetts) 1993: Harvard University Press; Latour, Bruno: Reassembling the Social. An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford a.o. 2007: Oxford University Press; Belliger, Andréa / Krieger, David J. (Eds.): ANThology. Ein einführendes Handbuch zur Akteur-Netzwerk-Theorie. Bielefeld 2006: Transcript.

- 13Cf. Schüttpelz, Erhard: Elemente einer Akteur-Medien-Theorie. In: Schüttpelz, Erhard / Thielmann, Tristan (Eds.): Akteur-Medien-Theorie. Bielefeld 2013: Transcript, 9-67. This brief presentation of the ANT approach is based on the corresponding section in Schlechtriemen, Tobias: “The Hero and a Thousand Actors. On the Constitution of Heroic Agency”. In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen 4.1 (2016), 17-32. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2016/01/03 .

- 14Cf. Latour, Bruno: The Pasteurization of France. London 1988: Harvard University Press, 252, FN 11 and Latour: Reassembling the Social, 2007, 53 ff., referencing Greimas, Algirdas Julien / Courtès, Joseph: Sémiotique. Dictionnaire raisonné de la théorie du langage. Paris 1979: Hachette Université. Regarding the notion of “actor” cf. also Latour: Reassembling the Social, 2007, 43-86.

- 15Cf. for this purpose the concept of ‘Assemblage’, as developed by DeLanda following Deleuze. DeLanda, Manuel: A New Philosophy of Society. Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. London / New York: Continuum 2006.

- 16The elements of a network can appear in three roles: as intermediaries, who do not change what they transport; as mediators, who translate, transform what they pass on; and as actors, i.e. those mediators who obtain clear outlines through figuration.

- 17His colleague Michel Callon refers to Serres, Michel: Hermes 3. La traduction. Paris 1974: Éd. de Minuit.

- 18This example lends itself because Latour develops his approach on Pasteur and lactic acid yeast, among others. Cf. Latour: The Pasteurization of France, 1988 and chapter 4: “From Fabrication to Reality. Pasteur and His Lactic Acid Ferment”. In: Latour, Bruno: Pandora’s Hope. Essays on the Reality of Science Studies, Cambridge (Massachusetts) / London 1999: Harvard University Press, 113-144.

- 19Online at: https://scienceheroes.com (accessed on 14.10.2019).

- 20Online at: https://scienceheroes.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=184&Itemid=183 (accessed on 14.10.2019).

- 21Wirtén, Eva Hemmungs: The Pasteurization of Marie Curie. A (meta)biographical experiment. In: Social Studies of Science 45.4 (2015), 597-610 also refers to this survey.

- 22‘Pasteurise’ is a common verb in very many languages and a constantly practised procedure, just as vaccination and basic hygiene measures shape our daily lives.

- 23Regarding these events, cf. Vallery-Radot, René: Louis Pasteur. Sein Leben und Werk. Freudenstadt 1948 [1900]: Schwarzwald Verlag, 441-455 and Geison, Gerald L.: The Private Science of Louis Pasteur. Princeton 1995: Princeton University Press, Kap. 6: “The Secret of Pouilly-le-Fort: Competition and Deception in the Race for the Anthrax Vaccine”, 145-176.

- 24At the last moment, two sheep were replaced with two goats and additionally six out of ten cows were vaccinated. Cf. Geison: The Private Science of Louis Pasteur, 1995, 147, FN 7.

- 25How this actor-network is shaped by each individual element, but how the elements in turn also only receive properties conditioned by the network, can be illustrated by the example of the syringe. Cf. Schlechtriemen: “The Hero and a Thousand Actors”, 2016, 23-25. I would like to thank Georg Feitscher for his help in developing the illustration.

- 26Part of this is that the focus is on the male science hero. In the film version of Pasteur’s life The Story of Louis Pasteur (from 1936, directed by William Dieterle), the rational scientist is juxtaposed with an irrational mystic, almost a witch figure.

- 27Anthropomorphisation here refers to the giving of a human form. In this respect, the concept is broader here than is usual in literary studies.

- 28The monument in Budapest commemorating the 1956 Hungarian National Uprising (erected in 2006 by the i-ypszilon group) symbolises the concentration effect of ordinary monuments in a very fitting way – and is itself aligned with the now empty site of the former Stalin monument. For the advice on this I thank Olmo Gölz.

- 29It is precisely this aspect of physical presentation that poses a problem in Muslim contexts – as does visualisation in general – which calls for other forms of representation such as writing or, at best, portraiture.

- 30Historical reconstructions have the additional difficulty that some of the actors involved did not survive or have not been preserved.

- 31The Sensory Ethnography Lab at Harvard University is specifically looking for alternative ways of representation. Online at: http://sel.fas.harvard.edu/index.html (accessed on 14.11.2019).

- 32Cf. the contributions to the discussion by Athene, Donald: “How many scientists does it take to make a discovery?”. In: The Telegraph, 17 September 2012; Athene, Donald: “In science today, a genius never works alone”. In: The Observer, 3 February 2013.

- 33Cf. Latour: Reassembling the Social, 2007, 128 f. Brecht, too, has his ‚worker who reads‘ ask about those blanked out in heroic stories: “Who built the seven gates of Thebes? / […] Young Alexander conquered India. / Was he alone? / Caesar defeated the Gauls. / Did he not have so much as a cook with him?” and closes with “So many reports / So many questions.” Brecht, Bertolt: Questions of a worker who reads. In: The Collected Poems of Bertolt Brecht. Transl. and ed. By Tom Kuhn and David Constantine w. the assistance of Charlotte Ryland. New York / London 2019: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 675. (Originally: “Wer baute das siebentorige Theben? […] Der junge Alexander eroberte Indien. / Er allein? / Cäsar schlug die Gallier. / Hatte er nicht wenigstens einen Koch bei sich?” und closes with “So viele Berichte / So viele Fragen.” Brecht, Bertolt: Fragen eines lesenden Arbeiters. In: Werke. Große kommentierte Berliner und Frankfurter Ausgabe. Vol. 12: Gedichte 2. Berlin / Weimar / Frankfurt a. M. 1988, 29.) I would like to thank Achim Aurnhammer for pointing this out.

5. Selected literature

- Aurnhammer, Achim / Klessinger, Hanna: “Was macht Wilhelm Tell zum Helden? Eine deskriptive Heuristik heroischen Handelns”. In: Jahrbuch der deutschen Schillergesellschaft 62 (2018), 127-149.

- Belliger, Andréa / Krieger, David J. (Eds.): ANThology. Ein einführendes Handbuch zur Akteur-Netzwerk-Theorie. Bielefeld 2006: Transcript.

- Bröckling, Ulrich: Das unternehmerische Selbst. Soziologie einer Subjektivierungsform. Frankfurt a. M. 2007: Suhrkamp, 35-38.

- Bröckling, Ulrich: Postheroische Helden. Ein Zeitbild. Berlin 2020: Suhrkamp.

- DeLanda, Manuel: A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. London, New York 2006: Continuum.

- Emirbayer, Mustafa / Mische, Ann: “What Is Agency?” In: American Journal of Sociology 103.4 (1998), 962-1023.

- Geison, Gerald L.: The Private Science of Louis Pasteur. Princeton 1995: Princeton University Press.

- Gölz, Olmo: “Heroes and the many: Typological reflections on the collective appeal of the heroic. Revolutionary Iran and its implications.” In: Thesis Eleven (2021), 1-19. DOI: 10.1177/07255136211033168.

- Greimas, Algirdas Julien / Courtès, Joseph: Sémiotique. Dictionnaire raisonné de la théorie du langage. Paris 1979: Hachette Université.

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: Aesthetics. Lectures on Fine Art. Vol. I. Transl. by T. M. Knox. Oxford 1975 [Repr. 2010]: Clarendon Press. (Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: Vorlesungen über die Ästhetik I. Frankfurt a. M. 1997: Suhrkamp.)

- Helfferich, Cornelia: “Einleitung: Von roten Heringen, Gräben und Brücken. Versuche einer Kartierung von Agency-Konzepten”. In: Helfferich, Cornelia / Bethmann, Stephanie / Hoffmann, Heiko / Niermann, Debora (Eds.): Agency. Die Analyse von Handlungsfähigkeit und Handlungsmacht in qualitativer Sozialforschung und Gesellschaftstheorie. Weinheim / Basel 2012: Beltz Juventa, 9-39, 10.

- Latour, Bruno: The Pasteurization of France. London 1988: Harvard University Press.

- Latour, Bruno: We Have Never Been Modern. Transl. by Catherine Porter. Cambridge (Massachusetts) 1993: Harvard University Press.

- Latour, Bruno: Pandora’s Hope. Essays on the Reality of Science Studies, Cambridge (Massachusetts) / London 1999: Harvard University Press.

- Schlechtriemen, Tobias: “The Hero and a Thousand Actors. On the Constitution of Heroic Agency”. In: helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu Kulturen des Heroischen 4.1 (2016), 17-32. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2016/01/03 .

- Schlechtriemen, Tobias: “The Hero as an Effect. Boundary Work in Processes of Heroization”. In: Falkenhayner, Nicole / Meurer, Sebastian / Schlechtriemen, Tobias (Eds.): Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories (= helden. heroes. héros. E-Journal zu den Kulturen des Heroischen. Special Issue 5 [2019]), 17-26. DOI: 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/03

- Schlechtriemen, Tobias: “Constitutive Processes of Heroic Figures”. In: Compendium heroicum. Ed. by Ronald G. Asch, Achim Aurnhammer, Georg Feitscher, Anna Schreurs-Morét, and Ralf von den Hoff, published by Sonderforschungsbereich 948 “Heroes – Heroizations – Heroisms” at the University of Freiburg, Freiburg 2022-08-19. DOI: 10.6094/heroicum/kphfe1.0.20220819.

- Schüttpelz, Erhard: “Elemente einer Akteur-Medien-Theorie”. In: Schüttpelz, Erhard / Thielmann, Tristan (Eds.): Akteur-Medien-Theorie. Bielefeld 2013: Transcript, 9-67.

- Serres, Michel: Hermes 3. La traduction. Paris 1974: Éd. de Minuit.

- Weber, Max: Economy and Society. A New Translation. Ed. and transl. by Keith Tribe. Cambridge (Massachusetts) / London 2019: Harvard University Press. (Weber, Max: Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Vol. 1. Tübingen 1956: J.C.B Mohr.)

- Wirtén, Eva Hemmungs: “The Pasteurization of Marie Curie. A (meta)biographical Experiment”. In: Social Studies of Science 45.4 (2015), 597-610.

6. List of images

- 1Pasteur-Denkmal, von Horace Daillion in Arbois (1901).Lizenz: Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0

- 2Akteur-Netzwerk von Pouilly-le-Fort, eigene Bildcollage von Tobias Schlechtriemen. Quellen und Lizenzen: Siehe Appendix Abbildungsnachweise

- 3Darstellung Louis Pasteurs mit seinem Mikroskop, Titelblatt von Real Heroes, Nr. 7, November 1942.Lizenz: Zitat nach § 51 UrhG

- 4Darstellung Louis Pasteurs mit seinem Mikroskop, Titelblatt von Real Heroes, Nr. 7, November 1942. (Vergrößerter Ausschnitt.)Lizenz: Zitat nach § 51 UrhG

- 5The actor-network is concentrated on Pasteur

- 6Visualisation of the processes of agency concentration and anthropomorphisation.